History: Survivors Land In Bermuda During WWII

[Part two of a series by Eric T. Wiberg]

During World War II there were 1,224 survivors landed in Bermuda from 24 ships [one US Navy, one Canadian Navy], between 17 Oct. 1940 and 27 February 1943.

Most of them were passengers on liner ships, followed by merchant sailors and then naval officers and men. The largest number of survivors were from the City of Birmingham [372 landed 1 July 1942, nine fatalities], and the Lady Drake [256 landed 6 May 1942, 12 fatalities].

The fewest were the schooner Helen Forsey and Melbourne Star with four each. Some men from the following ships were landed by air: Derryheen, USS Gannet, San Arcadio, and Melbourne Star. Only the following succeeded in rowing and sailing their way to Bermuda on their own: Helen Forsey [four Canadians] and James E. Newsom [nine Canadians].

While most survivors were picked up by other merchant ships, a number were rescued by naval vessels: Jagersfontein, City of Birmingham, Lady Drake, HMCS Margaree, British Resource, and USS Gannet.

Of those landed in Bermuda, most [12 ships / 243 men] came from British ships, five ships from USA accounted for 506 survivors, and three Canadian vessels for 299 persons. Other ships whose men landed in Bermuda were flagged to Uruguay, Sweden, Norway, and Netherlands [one ship each]. The longest survival voyages on open boats or rafts were experienced by six ships:

- Melbourne Star: 38 days

- Empire Dryden: 19 days

- Fred W. Green: 18 days

- San Arcadio: 15 days

- Helen Forsey: 12 days

- Stanbank: 10 days.

All the other 18 ships experienced voyages of nine days or less, with five ships’ crews on the water for one day or less. There were several weeks of particularly intense activity on shore, when several ships’ survivors arrived in Bermuda:

- End October 1940: Uskbridge 28 Oct and HMCS Margaree on 1 Nov 1940.

- Mid-March 1942: British Resource on 16 March and Oakmar on 24 March 1942.

- End April 1942: Agra and Derryheen on 22 April, Robin Hood 25 April, and Modesta 26 April, 1942.

- Early May 1942: Lady Drake 6 May, Empire Dryden 8 May, James E. Newsom, 10 May, and Stanbank 15 May.

- Mid-June 1942: West Notus 5 June, USS Gannet 7 June, Melbourne Star 10 June, L. A. Christiansen 12 June, and Fred W. Green 17 June 1942.

- Early July 1942: Jagersfontein 28 June, and City of Birmingham 3 July 1942.

Some, like the Derryheen, Maldonado, Uskbridge and West Notus, only had a portion of their crew landed in Bermuda, the others were rescued by ship or air and taken to different ports. Excluding the passenger ships, the average number of men per ship with survivors landed in Bermuda was 27 men.

Including all ships attacked around Bermuda [but excluding the Uskbridge and HMCS Margeree, which happened before Operation Drumbeat, which targeted the Hatteras/Bermuda area in January 1942], the attacks began on the 24th of January 1942 with U-106 under Rasch’s attack on the Empire Wildebeeste and ended on the 27th of February, 1943 with the attack by U-66 under Markworth on the Saint Margaret some 1,140 nautical miles from Bermuda.

Inside the 450-miles-from-Bermuda circle, the last attack occurred on the schooner Helen Forsey on the 6th of September 1942, by U-514 under Auffermann. That would mean that attacks inside the basic circle lasted 18 months, though of course the patrols lasted longer – into 1944 [see Axis attacks section].

The busiest month of attacks was April, 1942 with 20, followed by May 1942 with 15 and March 1942 with 14. The only months during which there were more than one attacks were January to July 1942, so it can be generalized that the sustained attacks lasted for the first seven months of 1942, though many patrols transited the area and occasional attacks were made [as in one a month] after that period.

- January 1942: 4

- February 1942: 9

- March 1942: 14

- April 1942: 20

- May 1942: 15

- June 1942: 11

- July 1942: 3

- August 1942: 1

- September 1942: 1

- February 1943: 1

Several dates stand out for having more than one attack [because of the use of German times to record attacks, and since German time is some six hours ahead of local, Bermudian time, and even more ahead of US East Coast time, attacks which occurred on the night of, say January 1st, might be recorded as having occurred on the 2nd of January, German time].

- 20 April 1942: 4: Agra, Empire Dryden, Steel Maker, and Harpagon

- 5 May 1942: 4: Lady Drake, Stanbank, Santa Catalina, and Freden

- 16 February 1942: 2

- 6 March 1942: 2

- 20 March 1942: 2

- 1 April 1942: 2

- 6 April 1942: 2

- 22 April 1942: 2

- 20 May 1942: 2

- 1 June 1942: 2

Canadian schooner James E. Newsom as seen from the deck of the Wawaloam; both schooners were sunk around Bermuda in WWII [photo courtesy Patsy Kenedy Bolling]:

There were 3,942 persons aboard 80 ships attacked by U-boats between 24 Jan 1942 and 27 February 1943 [13 months – excluding the Uskbridge, sunk off Iceland]. 957 were killed, or a mortality rate of roughly 25%. 2,985 survived. Of the survivors, 1,224 landed in Bermuda, which is roughly 41% of the survivors and 31% of the overall number of people attacked.

Out of 80 ships the majority, or 44, were steam ships laid out to carry general, or dry bulk cargo, as opposed to tankers or other types. There were eight motor ships which carried dry or general cargo, meaning 52 out of 80, or 65% were dry cargo ships. There were 21 tankers, of which 18 were the more modern motor tankers and three were steam tankers.

Thus 26% of the ships carried liquid cargoes, and most of them were motorized, whereas most of the dry ships were propelled by steam-driven machinery.

Additionally there was a US Navy minesweeper [USS Gannet], two schooners [Helen Forsey and James E. Newsom, both Canadian], and four passenger ships, of which three [Lady Drake, San Jacinto and City of Birmingham], were steam and one [Jagersfontein] was motorized. Some other ships, including the Fairport and Santa Catalina, carried passengers as well as freight.

Gross registered tonnage is different from deadweight tons: the GRT refers to the estimated weight of the ship in the water, with crew and equipment. Deadweight tons [DWT] refers to the amount of deadweight cargo that one can safely carry aboard the vessel.

Though readers might find it confusing, the deadweight capacity often exceeds the GRT, just as a mule may be able to carry more than its own weight. For example the British Resource weighed 7,209 GRT but carried 10,000 tons of benzene and white spirit.

There were only five ships [Frank B. Baird, Leif, Astrea, Anna, and Freden] between 1,191 and 1,748 tons, and two – both schooners – less than 1,000 tons: James E. Newsom at 671 tons and Helen Forsey at 167 tons. In the 9,000-ton range there were five ships, in the 8,000 range seven, and in the 7,000 range 11 vessels.

In the 6,000-ton range there were 10, the 5,000-ton range 14, and the 4,000-ton range only six. Between 3,000 and 4,000 tons were six ships and from 2,000 to 3,000 tons there were also six.

The total gross registered tonnage [GRT] of all 80 ships was 473,420 tons, so the GRT of the average ship would be 5,918 tons. The largest ships were San Gerardo [12,915], Victolite [11,410] and Montrolite [11,309]. There were four ships between 10,000 and 10,389 tons: Narragansett, Opawa, Jagersfontein, and Koll.

Generally the motor tankers were larger than their dry-bulk cousins: of the top 25 ships by tonnage, all except Lady Drake, Westmoreland and Hardwick Grange were either tankers or motor ships.

Out of 80 ships, 12 of them, or 15% were proceeding in ballast, in other words their cargo holds or tanks were empty except for water or sand, carried to keep them at a safe trim for ocean passages. The Halcyon, for example, was 3,531 tons and carried 1,500 tons of ballast to keep the ship steady in rough seas.

On the dry cargo side the cargoes were the most varied. They included coal, motor boats, military stores, beer, nitrates, motor trucks, chrome ore, cement, bauxite ore, phosphate, aircraft, locomotives, timber, manganese ore, mahogany, anthracite coal, refrigerated cargo [i.e. meats, butter], gas storage tanks, metal piping, flour, automobiles, wine, cereal, canned meat, wool, eggs, leather, fertilizer, explosives, bags of mail.

The variation continues, with ships carrying wheat, tungsten, nitrate, fuel in drums, steel, tires, small arms, fats, flax seed, tobacco, licorice, rugs, “war supplies,” construction equipment, cigarettes, tanks, lead, asbestos, chrome ore, concentrates, copper, resins, cotton, zinc concentrates, asphalt, burlap, rubber, linseed and tea.

On the tanker side, cargoes varied from petrol and paraffin to linseed oil, crude oil, fuel oil, aviation spirit, high grade diesel oil, gas oil, lubricating oil, gasoline, heavy crude oil, benzene and white spirit, kerosene, furnace oil, and petroleum products. The Helen Forsey was not a tanker, but rather a schooner, nevertheless she carried molasses and rum – presumably in barrels, not in bulk.

Ships attacked in the Bermuda area flew the flags of 11 countries: Britain [UK] [34 ships], USA [15], Norway [12], Canada [5], Sweden [4], Netherlands [3], Panama [2], Uruguay [2], Argentina [1], Latvia [1] and Yugoslavia [1]. Great Britain/UK accounted for 43% of ships lost in the region, the US 18% and Norway 15%, the others trailing significantly. Nine out of the 34 British ships, or 25% of them, were tankers.

The Canadian passenger/cargo ship Lady Drake; lost off Bermuda, survivors landed there:

In contrast only two out of 15 US-flagged ships, or 13%, were tankers. On the Norwegian side, five out of 12, or 42% were tankers.

Eleven ships left from New York, followed by 10 from various ports in the UK and 10 from Trinidad the three lead destination ports. Eight left Bermuda, seven left Curacao in the Dutch West Indies [invariably tankers loaded with petroleum or distillates], five from the US Gulf, and two from British Guyana. Five ships had made stops in Cape Town on their way from Middle Eastern and Indian ports. Four ships sailed from Halifax.

A number of ships – 10 – had last called at Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, to receive bunkers, or fuel, on long voyages from South America or South Africa. One sailed from Buenos Aires, four from Norfolk or Hampton Roads, Virginia. Three sailed from Panama [having left New Zealand or Australia], and four left Philadelphia.

One left from Savannah, another three from Saint Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. One ship left Portuguese East Africa [present-day Mozambique] and another from Recife, Brazil. Yet another sailed from Montevideo, Uruguay. Small ports like Turks & Caicos and Barbados were hailed by the schooners.

Ship destinations are somewhat clouded by the reality that if the ship is included in this study it was attacked by an Axis submarine and most likely never made it to port. Twelve were going to Halifax but 16 were going to Canada: two to St. John, as well as Sydney Nova Scotia and Montreal.

Sixteen as well were going to New York. Six were destined for Bermuda, one for Aruba, one for Baltimore, one for Iran, 11 to Cape Town and thence the Middle East or India. Two were destined for Venezuela, one for Cuidad Trujillo, Dominican Republic, three for Curacao Dutch West Indies to load petroleum products, one to Freetown Sierra Leone, one for Georgetown, British Guyana.

One was bound for Iceland, two for Norfolk or Hampton Roads Virginia, two for Philadelphia, one for Pernambuco, another for San Juan and yet another for Rio de Janeiro. One ship was bound for Texas City and another for Trinidad, and yet another for Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe.

The overall goal of this study was to include ships attacked within a roughly 450 mile circle around Bermuda, and the majority – 68 out of 80 – of the attacks occurred within that circle. There is a fine line between attacks which occurred off the US coasts of, say New England and Cape Hatteras, and Bermuda, and some ships were included whereas other, like USS Atik, were not.

For the most part, exceptions to the 450-mile-radius rule were made because the attacks occurred to the east and south of Bermuda, where they might not receive book-length treatment otherwise, and because Bermuda was the nearest land to the site where the ships were attacked, and was thus naturally an island to which the men may have set out to find salvation.

In other cases, the ships were included simply because, even though they were sunk far away [Uskbridge and Saint Margaret] the men were ultimately landed in Bermuda – or at least some of the survivors were. Since this study is about Bermuda under attack by U-boats and the men and women who landed there in World War II, then the story of the relevant attacks and rescues are included.

The average distance from Bermuda [excluding the Uskbridge], was 350 nautical miles [a nautical mile being 1.18 statute, or land miles]. The Modesta, sunk on 25 April 1942, was the closest to Bermuda at 121 miles, or ten hour’s steaming at 12 knots.

Next came the Harpagon the same week [20 April 1942] at only 164 miles distant, followed by the Raphael Semmes and Westmoreland, both 175 miles away and both sunk in June 1942. The Tonsbergsfjord was sunk 176 miles from Bermuda by the Italian submarine Enrico Tazzoli in March 1942. Astrea was sunk the same week by the same sub 194 miles from the island, and the Ramapo and Fred W. Green roughly 185 miles away.

There were 22 ships struck between 200 and 300 nautical miles from Bermuda and 33 between 300 and 400 miles away. Eight Allied merchant ships were attacked between 400 and 500 miles from Bermuda and four between 500 and 600 miles away [there may have been more if Cape Hatteras was included in this study – it was not].

These ships would have been sunk to the east and south of Bermuda, as the US mainland is only about 700 miles from Bermuda to the north and west. Five ships were sunk more than 600 miles from the island but were included in this study because their survivors were landed on Bermuda: Uskbridge and Saint Margaret.

The other three ships were the Pan Norway [743 miles away, sunk 27 January 1942], the Triglav [919 miles, sunk 9 July 1942] and the Athelknight, sunk 1,000 miles away on the 27th of May, 1942.

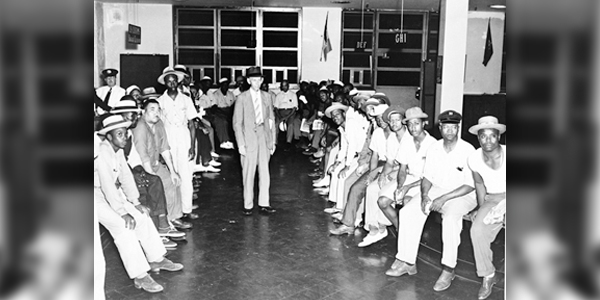

Captain Lewis P. Borum with members of the crew of the City of Birmingham in Bermuda:

The average or composite ship, based on the above analysis, would have been British-flagged, 5,918 tons, had 49 men and/or passengers on board and been carrying a general, or dry cargo. The most likely departure port would have been New York with destination ports in Canada and New York and the most likely time to have been sunk would have been April in 1942.

Typically the ship would be sunk by a German submarine 350 miles from Bermuda and 12 men would be killed in the attack. Of the balance, 15 of them would be landed in Bermuda and the others – 22 – would be landed elsewhere. Most of them would be rescued by other merchant ships or Allied naval ships, with a small percentage gaining salvation from sea airplanes.

Ultimately history is told not so much in statistics as through the eyes of the participants. Behind every number in this analysis were the tales of men and women caught unawares and pitched into the merciless North Atlantic. That the majority of them survived and a good number made landfall in Bermuda is a testament not only to the tenacity of their rescuers, who came across the seas and from the clouds, but also to the survivor’s good fortune.

For many the ordeal was not over, as they had to ship out on other vessels and brave the same seas again to reach North America or Europe.

As illustrated in these pages, the people of Bermuda, civilian and those in uniform, did the very best they could under the circumstances to welcome, accommodate, and resuscitate the survivors so that they could sally forth and adjust back into their individual roles in an all-consuming, global war which continued for a further three years.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Capt. Warren A. Brown, Sr., who immeasurably helped the author’s sailing career.

- Eric T. Wiberg is an author, historian, and researcher who has published nine books under four titles. His work can be followed on his personal website and on his U-Boats Bermuda blog.

Fisherman Mr. Gilbert Lamb of Cassia City, St David’s found the Helen Forsey survivors just off the East End of the island and towed them to Bermuda. He received an certificate from the Admiralty thanking him and though a technicality stopped him receiving the lifeboat as a gift he instead ‘purchased’ it for a nominal fee.

Mr. Lamb named it the ‘John Ralph’ after the Schooners captain who was one of the survivors. Mr. Lamb converted the lifeboat into a fishing boat which he used until he was unable to fish due to age and sickness.

Dear Sir – Is there any possibility that you have a photo of Mr. Gilbert Lamb and/or the HELEN FORSEY lifeboat which he re-purposed? If so I would be highly grateful. My research is sorely lacking in images of survivors and their rescuers in Bermuda. Many thanks in advance. Eric@ericwiberg.com.

I was there! first thing i did when i got off the boat was pour myself a cup of tea!

toodles!