Column: Where Do Your Clothes Come From?

[Column written by Bermuda Is Love]

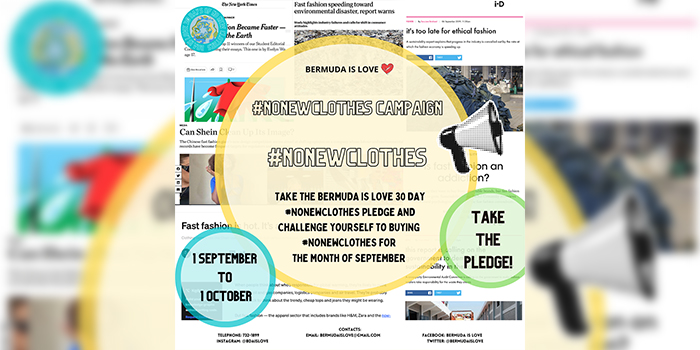

Bermuda Is Love has launched a campaign titled #NoNewClothes where we are challenging the public to purchase #NoNewClothes for the month of September. As part of the campaign, we will be publishing weekly articles highlighting the problem of fast fashion and what we as consumers can do about it. Please read our second article titled ‘Do you know where your clothes come from?’ and take the #NoNewClothes pledge.

How does fast fashion work?

The modern concept of ‘fast fashion’ is “the mass production of cheap quality clothing, with the term officially being coined in the 1990s by the New York Times, with Zara’s new accelerated production model being their inspiration – where clothes were taken rapidly from the design stage, inspired by Fashion Week, to their stores for anyone to buy. Fast fashion represents mass-produced trendy, low cost, and typically poor-quality clothing.”

Big names in the fast fashion industry include Pretty Little Thing, Boohoo, ASOS, Fashionova, Zara, Topshop, Shein, H&M, Primark, Forever 21, etc. These brands can turn clothing trends and styles seen on celebrities or worn on catwalks, into mass-produced garments in a matter of days. Fast fashion brands focus on rapidly producing high volumes of clothes to take advantage of popular fashion trends before they fade away. For example, Shein can get clothes from design stage to their store in 5-7 days.

Altogether, the fashion industry produces 100 billion items of clothing annually. But in order to produce such cheap clothes at a rapid pace, clothing production has had to be outsourced to countries where labour is cheapest. As a result, many fast fashion brands have outsourced their labour to countries where regulations are less strict or even non-existent. Thus, garment workers in these countries are forced to work in conditions that are unsafe, violate fundamental human rights, and fail to provide wages that are even close to a living wage [98% of garment workers do not earn a living wage]. The exploitation of garment workers allows fast fashion brands to sell large amounts of cheap clothing to consumers in the West. Clearly, the fashion industry is a broken system. But how exactly did we get here?

The history of the fast fashion industry

Before the 1800s, all fashion was slow, as clothes were often tailored to the individual and designed to last a lifetime. Individuals had to source their own materials, make their own clothing, and repair them when necessary. However, the Industrial Revolution changed the entire fashion industry with the invention of the sewing machine and factory line.

The sewing machine gave people the ability to mass-produce clothes, creating an abundance of clothing which contributed to the fall in price of clothing. As a result, clothing became something that people started wearing for style, not necessarily out of necessity. As the fashion industry began to change, clothing allowed individuals to present themselves more through style, trends, and class, and no longer had to wear clothes solely because of features of practicality, such as durability.

The first sweatshops

As a result of the Industrial Revolution, the first textile sweatshops began to appear in London, UK and quickly spread to other continental European cities such as Paris, France. In both London and Paris, sweatshops would employ mostly impoverished immigrant women and children who had very few job alternatives. During this time in Europe, the concept of labour unions and child labour law were non-existent until the passing of the Factory Acts and the introduction of compulsory schooling in the beginning of the 20th century.

Rise of the department store

As the abundance of clothing rose, so did the popularity of what was called ‘ready-to-wear’ fashion – clothing that was sold in finished condition in standardized sizes, as opposed to clothing that needed to be tailored. Department stores in the early 20th century, took advantage of the tremendous increase in demand for mass-produced clothing. With the massive waves of European immigrants moving to the U.S in the 20th Century, New York City became a new hub for cheap production, where hundreds of workers in factories, mostly women, would hunch over long rows of sewing machines for hours at a time for little pay.

It was only until the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911, where 146 garment workers [123 women and 23 men] died from fire, smoke inhalation, and falling or jumping to their deaths that worker conditions in the U.S began to change. The tragedy of 1911 became a starting point for women’s unionization movements and legislation improving fire safety standards in the US. However, this tragedy was only one of many industrial disasters that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of exploited workers in the early 1900s.

Underground sweatshops

After World War II, the influx of Asian immigrants to California made Los Angles the new centre for sweatshops. While unionisation and stricter government regulations shut down many open sweatshops, many smaller factories simply went underground. As a result, in 1995, 72 Thai garment workers were found working as modern-day slaves in a hidden sweatshop in suburban Los Angeles. These exploited workers were recruited from impoverished Thai rural villages with the promise of a better future in America. However, they were held captive to sew clothing for 17 to 22 hours per day. This discovery provided a wakeup call for many in the fashion industry and served as a catalyst for global awareness regarding modern day slavery and human trafficking.

Outsourcing of production

With the rise of labour costs in Western countries in the 21st century, garment sweatshops have now been outsourced to various countries in the Global South. These countries often lack stringent labour laws and unions. Thus, by outsourcing their production, fast fashion companies are able to reduce their costs by taking advantage of vulnerable populations which keeps garment workers entrenched in poverty. Sadly, this exploitation of garment workers continues to affect mainly women and children in factories and sweatshops today, nearly two centuries since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Women currently make up 80% of all garment workers in the Global South. Many of these women have no other source of income, are underpaid, and do not receive compensation for overtime, sick pay, or maternity leave. The average garment worker is paid a piece rate of between 2-6 cents per piece working between 60-to-70-hour weeks with a take home pay of about $300 dollars. In addition, garment workers often work in unsafe conditions, with an absence of any fundamental human rights protections. For example, some of the world’s leading fashion brands are complicit in the forced labour and human rights violation of Uighur people in China.

Moreover, the collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013, and the documentary The True Cost [2015] further highlights the problem within the fashion industry, how it profits off the exploitation of garment workers, and how it contributes to the climate crisis. The International Labour Organization estimates that “250 million children, 61% in Asia, 32% in Africa, and 7% in Latin America are employed in sweatshops with women making up 85% to %”. Therefore, the importance of ensuring that garment workers are protected and treated fairly is great.

Our role as ethical consumers

As consumers our role is to demand that our clothes be ethically and sustainably made. While any kind of change may seem impossible in an industry that has continuously profited from the exploitation of the most vulnerable populations throughout the course of history, there are ways in which we can demand change by changing our own habits of consumption.

We as consumers have power; we can demand change by boycotting products that violate human rights, that destroy the planet, and we can let big fast fashion brands know that we will not support or buy products from them that have been produced by exploiting garment workers in the Global South. Change can also occur through joining other anti fast fashion organisations including Fashion Revolution, Sustainable Fashion Week, and Re/make [which is where we found the inspiration for the #NoNewClothes campaign].

#NoNewClothes represents Bermuda Is Love’s manifesto that we will not condone any kind of consumption unless it is sustainable and ethical. We all have a responsibility to uphold human rights and ensure that others are treated with respect. And we must recognize that it is the exploitation of foreign workers in the Global South that allow those in the West to buy cheap clothes in the first place. Our ease of life is provided by the exploitation of others. This is not right. We should not be living off the backs of others or think that because exploitation exists in some far-off country that our responsibility is somehow limited. If we have the power to act and demand change then we must do so. We are all citizens of earth, and we all deserve to be treated as such.

Sources

- Retrieved from SANVT

- Retrieved from Matterprints

- Retrieved from Fashionista