Column: Bermuda’s Royal Naval Tanks, Part 1

[Column written by Dr. Edward Harris]

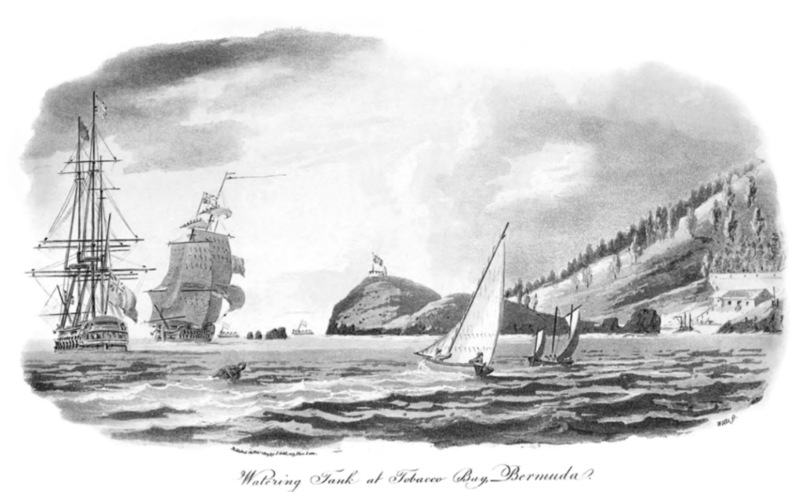

One of the earliest artistic views of Bermuda appeared in 1803 in The Naval Chronicle and is a scene of the commodious Murray’s Anchorage to the north of St. George’s Island, with Fort St. Catherine and its rearward hills in the background. It is an aquatint, which is a form of intaglio printmaking that relies on areas of toning rather than hard lines. The illustration was accompanied by a description by a man using the pseudonym “Porgay,” which may be a variant spelling for the local fish, the Porgy.

The identity of that possibly fishy individual is not known, although he later wrote about Bermuda and the War of 1812 and the capture by the British of the United States frigate, USS President, in the final moments of the conflict in January 1815. Those articles appeared in Volumes 33 and 35 of the Naval Chronicle [1815 and 1816], but as Porgay is not mentioned by a real name in the journal. However, the papers are referenced to him bibliographically, it is likely he was known to the editor of that journal, who thanked several other pen-name correspondents as well.

The reason for a renewed interest in the 1803 aquatint was the late 2023 acquisition by a friend of a post-1808 copy of it and the appearance of an even later copy, perhaps post-1815, in the guise of a watercolour by the artist, Henry Bonham Bax. The three pictures will be presented and discussed in this note in four parts, but first a little context may be of assistance to start.

Bermuda after the Treaty of Paris

Settled fully in 1612 and until 1684 the Island was basically the “company town” of the Bermuda Company, a prototype of the modern corporation, like the Honorable East India Company. From the latter date, the British Government took possession of the defunct Company, but the Island continue its own internal rule, with its parliament, one of the oldest in the world. While having some sympathy with the rebels of the British settlements on the east coast of North America, Bermuda remained an English possession. The Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the American War of Independence, portended great changes for the Island, as the Royal Navy lost all its seaports on the North American continent, except for Halifax in the north.

From 1783, military and naval surveys were made as the British Government realized the strategic value of Bermuda, halfway between Nova Scotia and their bases at Jamaica, Antigua and Barbados. Throughout most of the 1790s, Major Andrew Durnford, Royal Engineers, and Captain Thomas Hurd, Royal Navy, respectively, surveyed the land for fortification sites and the ocean for channels into the harbours, as Bermuda was bound by a rampart of reefs. In the decades following 1809, a great dockyard was erected in the western Ireland Island, while in the east, half a dozen large forts were emplaced to protect “Hurd’s Deep” [now The Narrows], the main ship channel through the reefs to the dockyard anchorage Grassy Bay.

Once Hurd discovered the channel, in 1795, a ship of the line, HMS Cleopatra, made the first transit into Murray’s Anchorage, named for the admiral on the “River St. Lawrence & Coast of North America & West Indies Station” at the time. In the same year, a small depot was established at the town of St. George’s for the Royal Navy, the function of which was largely transferred to the Dockyard at Ireland Island, so the Royal Navy was ultimately in Bermuda for two centuries [1795–1995].

In 1802, Vice Admiral Sir Andrew Mitchell, BT, KB, assumed command of the Station, by which time, the Naval Wells for potable water had been established on the north shore of Devonshire Parish, within sight of Ireland Island [earmarked by Vice Admiral the Hon. George Murray for the eventual dockyard], a few miles distant to the west. The “Watering Tanks” at Tobacco Bay on the north coast of St. George’s Island had also been established, but they were tanks with cemented catchments for rain water, as opposed to the ground water of the wells at “The Watering Place” in Devonshire. The name of a private home, “Seven Wells”, on the north shore of the parish signifies the location of the Watering Place.

While Bermuda has no rivers, it possesses a certain amount of ground water, which is the result of rain percolated through the largely soft and porous Bermuda stone, coming to rest for several feet on the underlying salt water of the ocean which permeates the limestone cap of Mount Bermuda. As the height and weight of the freshwater increases, it moves horizontally to seep into the sea, and thus may be captured in wells on the coast in certain places like Devonshire. About the same time, the famous Rosia Water Tanks were built at Gibraltar later, with Bermuda, one of Britain’s four “Imperial Fortresses”. The Gibraltar and Bermuda tanks were largely demolished or much altered in recent decades.

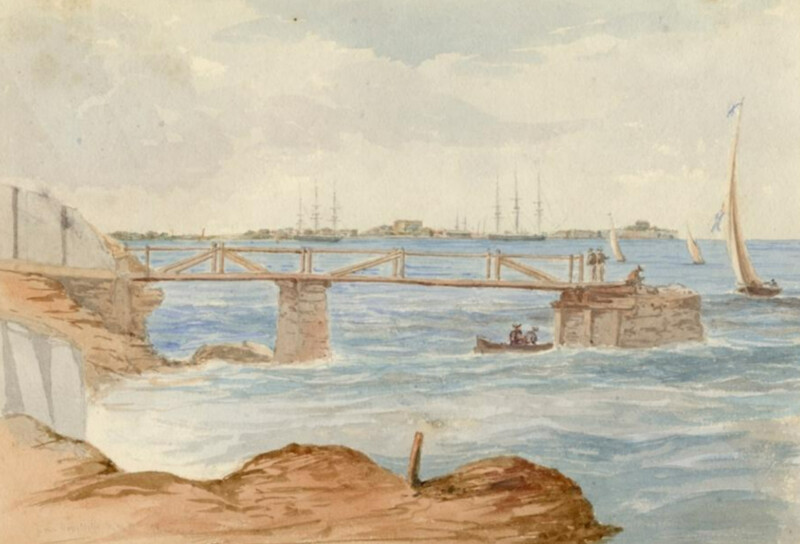

Fig. 1. The quay for the Royal Navy’s “Seven Wells” in Devonshire Parish, with the Dockyard in the background, recorded as “The Watering Place” in Hurd’s Survey of 1789–97. The Dockyard is in the background. [Michael Seymour 1845. Fay & Geoffrey Elliott Collection, Bermuda National Trust.]

Porgay’s text below, and the image from the Naval Chronicle give further context in the post-Hurd times in the early 1800s.

Description of Plate CXVII: Porgay’s 1803 text, as extracted from the Naval Chronicle, Vol. 9 [no. 2] 1803, pp. 109–111

We are indebted to a Correspondent that uses the signature PORGAY, for the annexed View and the following description, which we give in his own words:

The annexed view of the Watering Tank, at Tobacco Bay, Bermudas, was taken from Murray’s anchorage on the north side of the islands, where a line of battle ship is at anchor, another coming in, having passed Catherine’s Point, and a fishing-boat in the foreground.

Of this island, or rather group of islands, I am unable to give more than an outline, but hope the few following observations will occasion your receiving some communication on the subject from others better acquainted.

Various accounts are given of the time of their discovery, but it appears they remained uninhabited, till about the year 1609, when Sir George Summers was wrecked on them.

In former times the Bermudas must have been held in great dread by the navigator, from the tempestuous weather in their neighbourhood. In the Tempest of Shakespeare, we find Prospero addressing Ariel as follows:—

Pros. Of the King’s ship, The mariners, say how thou has dispos’d, And all the rest of the fleet?

Ariel. Safely in harbour Is the King’s ship; in the deep nook where once Thou call’dst me up at midnight to fetch dew From the still vex’d Bermoothes.

And Donne, who wrote two centuries ago, in describing the effects of a storm, says,

Fig. 2. Plate CXVII: “Watering Tank at Tobacco Bay, Bermuda. Published 28 Feby 1803 by J. Gold, 103, Shoe Lane [London]. Wells, Jo. [John: engraver]”

Compar’d to these storms death is but a qualm, Hell somewhat lightsome, the Bermudas calm.

That these islands are frequently visited by storms cannot be denied, but whatever fears were formerly entertained on approaching them, when nautic science was less cultivated—it is now considered as fraught with much danger.

In the American rebellion they were sometimes visited by our men of war, during which period the Cerberus frigate was wrecked on the south side, at Castle Harbour; Murray’s anchorage was then unexplored; and it is to the scientific knowledge and sedulous exertions of Captain Thomas Hurd, of the Navy, who for some years previous, and about the beginning of the late war, was employed on this intricate survey, that the nation is indebted for its completion.

The geographical situation of the Bermudas, as well as of the many banks and reefs, which on the north, east, and west sides, extend to the distance of three, four, and five leagues, has been ascertained by Captain Hurd with the same fidelity as the channels to the harbours.

In 1795, Admiral Murray, in the Resolution, with other line of battle ships, having passed through the channel by Catherine’s Point, anchored on the north side, from which circumstance the anchorage acquired his name.

The navigating a 74 gun ship among the rocks in this truly intricate channel, where, from the translucency of the water, they could be discerned but a few yards on either side of her bottom, served to confirm an opinion I had always heard as well as entertained of the cool nerves of the late Admiral. And it must have been highly flattering to the persevering talents of his pilot, Captain Hurd.

During the subsequent part of the war, Murray’s Anchorage was a frequent rendezvous for the line of battle ships and frigates under the command of the late worthy Admiral [George] Vandeput [d. March 1800].

From about east round by south, to west south-west or west, the Anchorage is sheltered by the land. To the north, north-east and north-west, it is exposed to a long range of sea, but which is considerably diminished by reefs forming a barrier in these directions, though at several miles distance. Line of battle ships and frigates have encountered very heavy gales in this Anchorage without accidents.

Fig. 3. A Bermudian Pilot in a white uniform, at the tiller of a pilot boat or dinghy. [Gaspard Le Marchant Tupper 1857. Fay & Geoffrey Elliott Collection, Bermuda National Trust.]

Among the reefs there is a passage to sea, called, the “North Rock Channel,” through which several frigates have passed when eastern winds have rendered the channel by St. Catherine’s Point impracticable.

The bottom in Murray’s Anchorage is at a moderate depth, of a kind of tough pipe-clay.

About a mile from where the men of war anchor, a tank has been built at Tobacco Bay, to collect rain water for the Navy. But water can be procured at the wells where frigates anchor with safety, some miles westward of Murray’s anchorage [The Watering Place in Devonshire].

From Tobacco Bay, it is a short mile across to St. George’s Harbour, where, during the war there was a small depot of stores for the American squadron. Into this harbour sloops of war can pass with safety. A twenty-four gun ship entered it without accident.

Pilots are to be procured by making a signal off Castle harbour, who generally anchor vessels in a place called the Hole, should the wind or tide be adverse for entering St. George’s harbour. The former of which even at spring tides does not rise about six feet.

The length of the Bermudas from Wreck Hill, the western part of them, to St. David’s Head, in the opposite quarter, is about six or seven leagues. Their breadth not near as much. It is not here meant to include the banks and reefs.

They should be approached, if possible, from the S.W. quarter, as on their south side there are no sudden dangers, nor indeed any, but the S.W. breakers, which are not above a mile from the land. It is not uncommon before you make the land, to first distinguish the white houses above the horizons. Porgay.

The Bermudian pilots are men of colour, very prompt and intelligent in their business, particularly since they have been accustomed to men of war. They generally take their station on the forecastle or bowsprit, where they can distinguish every rock, by the transparency of the water, luffing and bearing away with great rapidity, bringing rocks from one bow to the other in a short minute.**

A Captain in a small frigate under sail off the island, was anxious to know of one of these active fellows, whether he could carry the ship into St. George’s harbour. The pilot paused a little, but said, “he believed he could find room for her keel among the rocks without touching them.” The Captain made no more inquiries, feeling perfectly satisfied in being conveyed to Murray’s anchorage.

- Dr. Edward Cecil Harris

Read More About

Category: All