US Ruling On $20M Secret Payment

A US Appeals Court yesterday [Jan. 11] threw out a lower court ruling favouring a former Tyco director in the latest chapter of a decade-long legal dispute involving a secret $20 million payment authorised by the one-time Bermuda firm’s disgraced CEO.

A US Appeals Court yesterday [Jan. 11] threw out a lower court ruling favouring a former Tyco director in the latest chapter of a decade-long legal dispute involving a secret $20 million payment authorised by the one-time Bermuda firm’s disgraced CEO.

Former director Frank Walsh was sued by Tyco in connection with the firm’s June, 2001 $9.2 billion acquisition of The CIT Group Inc.

Tyco had incorporated and attached an Agreement and Plan of Merger stating that no one other than bankers Lehman Brothers and Goldman, Sachs & Co. were entitled to an investment banking or finder’s fee for representing the firm in the transaction.

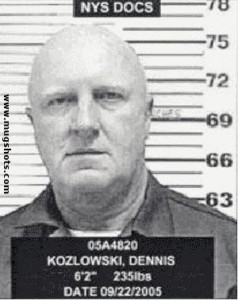

But at the time that he signed the registration statement, Mr. Walsh knew that L. Dennis Kozlowski [pictured], then Tyco’s CEO, had proposed that, if the transaction was successfully completed, he would be paid a finder’s fee for having arranged a meeting between the companies to discuss a possible merger.

In fact, after the transaction was consummated, Mr. Kozlowski caused Tyco to pay Mr. Walsh a $20 million “finder’s fee” in the form of $10 million in cash and a $10 million charitable contribution to a foundation chosen by the director.

“Mr. Walsh served as chairman of Tyco’s compensation committee and a member of Tyco’s corporate governance committee,” said Thomas C. Newkirk, the US Securities & Exchange Commission’s then Associate Director of Enforcement, after details of the secret payment were first revealed in 2002. “Shareholders entrusted him with the responsibility of watching out for their interests in Tyco’s boardroom and executive suite.

“Instead, Mr. Walsh himself took secret compensation and kept those same shareholders in the dark.

“Once again, the Tyco investigation has uncovered clandestine payments and hidden deals,” Mr, Newkirk said. “Once again, the evidence demonstrates that Tyco’s top management viewed Tyco’s assets as their own.”

Tyco relocated its corporate headquarters to Bermuda from the US in 1997 although the company’s main business interests continued to be run out of Exeter, New Hampshire and New York.

Former CEO Mr. Kozlowski — jailed for eight years in 2005 for defrauding the company of tens of millions of dollars — became notorious for his extravagant lifestyle supported by the booming stock market of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Allegedly, Mr. Kozlowski — who spent considerable time in Bermuda when the firm was headquartered here — had Tyco pay for his $30 million New York City apartment which included $6,000 shower curtains and $15,000 “dog umbrella stands.”

Shamed Washington DC lobbyist Jack Abramoff — sent to prison on mail fraud and conspiracy charges — detailed his dealings with Mr. Kozlowski and Tyco at the time the firm was run out of Bermuda in his recent bestseller “Capitol Punishment”, calling it one of the most “reviled and corrupt” corporations in the world.

Tyco redomiciled to Switzerland from Bermuda in 2009.

The SEC pursued a civil action against Mr. Walsh in 2002. Without admitting or denying the allegations in that complaint, Mr. Walsh consented to the entry of a final judgment permanently enjoining him from violations of the US federal securities laws, permanently barring him from acting as an officer or director of a publicly-held company, and ordering him to pay restitution of $20 million.

The ruling issued yesterday [Jan. 11] by New York’s United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, was largely based on arguments by Tyco that “that Walsh’s [fiduciary] breach was dishonest under Bermuda law.”

A Summary of the US Court Of Appeal Judgement Appears Below:

Tyco International Ltd., a Bermuda corporation, sued Frank E. Walsh, Jr., a former member of Tyco’s board of directors, for breaching his fiduciary duty to Tyco by secretly receiving a $20 million payment from Tyco in connection with Tyco’s acquisition of The CIT Group, Inc., and failing to disclose his financial interest in the acquisition.

Tyco now appeals from a judgment in Walsh’s favor entered after a bench trial at which the District Court determined that, under Bermuda law, Tyco’s board of directors had implicitly ratified the payment to Walsh, even though Walsh had breached his fiduciary duty to the company.

We need not here decide whether Walsh’s breach of fiduciary duty was capable of ratification because, even if we were to resolve that issue in Walsh’s favor, we conclude that, under Bermuda law, Walsh’s breach could be ratified only by Tyco’s shareholders, not its board of directors. It is undisputed that Tyco’s shareholders did not ratify Walsh’s breach. We therefore reverse the judgment of the District Court.

“[This Court] review[s] the [D]istrict [C]ourt’s findings of fact after a bench trial for clear error and its conclusions of law de novo.” Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Retail Holdings, N.V., 639 F.3d 63, 68 [2d Cir. 2011]. We assume the parties’ familiarity with the underlying facts, the procedural history of this case, and the issues on appeal.

This appeal presents the question whether, under Bermuda law, Tyco’s board of directors was capable of ratifying a fellow director’s breach of the fiduciary duties of loyalty and honesty to the company. In resolving that question in Walsh’s favor, the District Court appears to have conflated the issue of whether the board could ratify the CEO’s decision to pay Walsh without first securing board approval with that of whether the board could ratify Walsh’s failure to disclose his interest in the acquisition.

As the District Court observed, “the directors of a corporation can ratify an act entered into on behalf of a corporation, if they are authorized to approve such an act on behalf of the company.” Tyco Int’l Ltd. v. Walsh, 751 F.Supp.2d 606, 621 [S.D.N.Y. 2010] [citing Peter Watts & F.M.B. Reynolds, Bowstead & Reynolds on Agency ¶ 2-078 [18th ed. 2006].]

This understandable conclusion reflects a valid principle of Bermuda law relating to fiduciaries. As one treatise on English law2 describes it, “those to whom the duties are owed may release those who owe the duties from their legal obligations and may do so either prospectively or retrospectively, provided that full disclosure of the relevant facts is made to them in advance of the decision.” Paul L. Davies, Gower & Davies’ Principles of Modern Company Law 437 [7th ed. 2003]. Because the board was authorized to approve payments to a director under Tyco’s Bye-Laws, it presumably could have ratified such payments, including the $20 million payment to Walsh.

In addition to finding that Walsh wrongfully received the $20 million payment, however, the District Court determined that Walsh breached his fiduciary duty to Tyco by failing timely to disclose “that he stood to benefit personally from [the board's] approval of Tyco’s acquisition of CIT.” Walsh, 751 F. Supp. 2d at 621. Under Bermuda law, those duties were owed to Tyco’s shareholders, not its board of directors. See Miller v. Bain, [2002] 1 B.C.L.C. 266 (Ch.), ¶ 67, 2001 WL 1743253 ["It is well established that whilst a company is solvent, its directors owe the company a fiduciary duty to act bona fide in the company's interest, and that `the company' in this context is understood to mean the shareholders, present and future, as a whole."].

Accordingly, Bermuda law contemplates that “[o]nce a breach has occurred, . . . only a decision of the shareholders in general meeting can effect a release.” Davies, supra, at 437; see Regal [Hastings] Ltd. v. Gulliver, [1967] 2 A.C. 134 (H.L.), 140, 150, 1942 WL 12815 [finding that an unauthorized allotment of shares by directors could be ratified “by a resolution [either antecedent or subsequent] of the Regal shareholders in general meeting”]; Partco Grp. Ltd. v. Wragg, [2002] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 320 (Q.B.), ¶ 41, 2001 WL 1040203 ["I accept that, as a general rule, fraud or breach of fiduciary duty on the part of a director can only be ratified by the company in general meeting and upon full disclosure of the relevant facts."]

We are unaware of any authority in support of Walsh’s suggestion that Bermuda law permits a board of directors to circumvent this rule, through its bye-laws or otherwise. Walsh has not pointed to a single case in which a court has upheld a board of directors’ retroactive ratification of a director’s breach of fiduciary duties under Bermuda law [or, for that matter, English law]. Assuming for the sake of argument that such breaches can be ratified at all, therefore, only Tyco’s shareholders would have been authorized to ratify Walsh’s breach, and they did not do so.

Pointing us to treatises, Bermuda statutes, and caselaw, Tyco urges us to conclude that Walsh’s breach was dishonest under Bermuda law, precluding ratification even by shareholders. See, e.g., Davies, supra, at 440-41; Bermuda Companies Act § 97(4); Shaker v. Al-Bedrawi, [2001] EWHC (Ch) 159, ¶ 143, 2001 WL 825485.

Having concluded that Bermuda law does not permit a board of directors to ratify a director’s breach of fiduciary duties and, at the very least, requires that the shareholders ratify such a breach, we need not address that issue.

The District Court resolved the principal damages issues in the event that Tyco prevailed on appeal. Neither party contests the District Court’s resolution of damages, and we need not further address it. The parties dispute only whether the District Court determined that it would award consequential damages to Tyco relating to its retention of Boies, Schiller & Flexner LLP. We leave this question for the District Court to address on remand.

We have reviewed the parties’ other arguments and find them to be moot or without merit. The judgment of the District Court is REVERSED and REMANDED for further proceedings consistent with this order.

Read More About

Comments (6)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Articles that link to this one:

- Ex-Tyco CEO Kozlowski Settles $500M Dispute | Bernews.com | August 11, 2012

Fraudulent business practices in Bermuda? This just can’t be.:)

Always trying to run Bermuda down don’t be stupid. You sound like BOB RICHARDS UBP/OBA

Actually the fraud was committed by US businessmen most likely in the US and they got tripped up because the company was incorporated under Bermuda law which makes it difficult for directors to approve a breach of fiduciary duty without disclosure to shareholders and shareholder approval. Under Delaware, and other state corporation laws, it is quite possible for the directors of a corporation to ratify such a breach without shareholder knowledge or approval. In this particular instance, Bermuda law saved the day for the shareholders. Perhaps things don’t always work out this way but in this instance it did.

Thanks for the clarification, and sorry for jumping tho the wrong conclusion.

A bunch of hypocrite. Aways trying to steal money it is in you all DNA.