When Bermuda Was “Thurber Country”

Bermuda was humourist James Thurber’s world — and for almost three decades he welcomed readers of “The New Yorker” to it in a series of witty dispatches from the island.

Bermuda was humourist James Thurber’s world — and for almost three decades he welcomed readers of “The New Yorker” to it in a series of witty dispatches from the island.

Best known for such stories as “The Secret Life Of Walter Mitty”, his much lauded series of fables featuring anthropomorphic animals and fairy tales including “The Thirteen Clocks”, Ohio-born author and illustrator James Thurber [1894-1961] remains one of the most popular and beloved comic writers in the history of American literature.

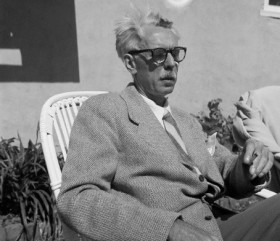

A longtime fixture at “The New Yorker” magazine — where he celebrated the comic frustrations and eccentricities of ordinary people in his short stories and surrealistic drawings — Thurber began paying annual visits to Bermuda in 1931 [he is pictured above at the Fourways Inn during a 1950 vacation on the island].

“James Thurber’s eye for the ridiculous, the pompous or the bigoted continues to be as keen as ever — and that’s about as keen as a Toledo blade,” said veteran Bermuda journalist Marian Robb when she interviewed the writer for the “Mid-Ocean News” in 1957.

“The tall and easy-mannered gentleman with a ruddy face and thick sheaf of frosty hair has a mind like a dragon-fly — darting, probing, hovering and diving, poised on shimmering wings above some murky depth or weaving impromptu patterns in the startled air.

“No subject it attacks is ever quite the same again.”

Although he and his wife rented homes in various parts of the island during their pilgrimages to the island, Sandys Parish became his favourite haunt.

When he was in residence at the West End, Bermudians jokingly took to referring to Sandys as “Thurber Country” after the title of a benchmark 1949 collection of his satirical writings.

James Thurber with wife Helen on wall at “Felicity Hall”, Somerset, Bermuda

Bermuda began to feature in Thurber’s writing shortly after the New York-based writer made the island his winter retreat.

In a satirical essay entitled “Extinct Animals Of Bermuda”, Thurber conjured with such imaginary creatures as the woan ["scarcely larger than a small blue cream pitcher, the woan had three buttons on the vest of his Sunday suit, and was given to fanning his paws at spindrift"] and Hackett’s Gorm ["a tailless extravertebrate about whom only one fact has survived the centuries: he was discovered by Mr. and Mrs. W. L. Hackett and their daughter Gloria."]

“I made them up,” Thurber told Marian Robb of the fanciful animals in his Bermuda bestiary, “but many people took it seriously.”

He became great friends with West End residents Ronald Williams, wife Jane and their children, even contributing on occasion to “The Bermudian” magazine which his Sandys neighbour founded and edited for many years.

“I didn’t like the last piece I wrote for you very much, but they will improve with the coming of Spring and the ending of our long cycle of disasters,” he wrote to Mr. Williams from his Connecticut home in 1950. “I would like to bring Helen to Bermuda but can’t very well leave her mother, who is likely to collapse again at any minute.

“The first thing we will do, when we can, is to get down there …”

Among other locally flavoured pieces, Thurber once wrote a mordanantly humorous poem inspired by a bee sting he received while on the island entitled “Bermuda I Love You”,

“Hark my child to a tale of disaster

Of yards of gauze and casts of plaster,

Of festering lip and shattered feet,

Of hearts that suddenly cease to beat.

Henry O. Jones was a bike-riding fool

And what was that liquid in that little pool

That turned his socks red

And moistened his head?

Listen my child, it was not milk or mud,

It was not Scotch or rye; it was red, it was blood.

Maribel Smith scratched her hand with a stick.

She didn’t bleed much, and she didn’t feel sick.

There was just a small cut on one of her paws

But in forty-eight hours she could not move her jaws.

In five or six days they were lighting the candles

And they bought her a box with bright silver handles.

Or consider the case of Herbert A. Dewer,

Healthy at noon and by nighttime manure.

Herb would have said you were certainly silly

Had you told him that he would be soil for a lily.

Or list to the tale of Harrison Bundy,

Here on Tuesday, gone on Monday.

And over the grave of Beth Henderson sigh;

She died from the bite of a common house fly.

And here close beside the murmurous sea

Lies a tall nervous writer stung by a bee.

Oh, Bermuda is lovely, Bermuda is bright,

But beware its claws and beware its bite.

Remember H. Dewer, remember H. Mundy,

Remember Sic Transit Gloria Mundy.”

He also drafted his darkly whimsical children’s classic “The Thirteen Clocks” [1950] on the island, saying in the introduction: “I wrote [this book] in Bermuda, where I had gone to finish another book.

“The shift to this one was an example of escapism and self-indulgence. Unless modern Man wanders down these byways occasionally, I do not see how he can hope to preserve his sanity.”

Described by “Los Angeles Times” critic Sonja Bolle as “an eccentric children’s story that took apart and lovingly reconstructed the fairy tale long before William Steig wrote ‘Shrek’ or William Goldman penned ‘The Princess Bride’ … ‘The Thirteen Clocks’ is the first book I remember loving, and it is one of the few books I managed to wrest from my family’s library and preserve through all the mundane disasters of my life. Everything about it is dear to me …”

And in a recent edition of “The Thirteen Clocks”, children’s author Neil Gaiman says it is “ … probably the best book in the world.”

He goes on to say of the Bermuda-penned children’s novel, “And if it’s not the best book, then it’s still very much like nothing anyone has ever seen before, and, to the best of my knowledge, no one’s ever really seen anything like it since.”

Neil Gaiman narrates promotional video for “The Thirteen Clocks”

During the final years of his life, Thurber worked on an on-again, off-again basis on a play called “Welcoming Arms” which was set at a Bermuda house called “Serenity Hall” where vacationing Americans have come to seek peace and quiet.

“Instead, all hell breaks loose,” the writer told Marian Robb.

First announced for the 1956 Broadway season but never produced, Thurber was said to be insistent that the production designers visit Bermuda so “they could see how to make authentic sets.

“For one thing, they must record the night song of the tree-toads.”

Thurber’s health declined precipitously towards the end of his life.

His sight — he had been blinded in one eye as a result of a childhood accident — deteriorated to the point where he had to dictate stories and letters to a secretary rather than write them himself. He had to abandon his idiosyncratic — and instantly recognisable — cartoons altogether.

He died in 1961, at the age of 66, due to complications from pneumonia, which followed upon a stroke suffered at his home.

In 1969-1970 a TV series based on Thurber’s writings and life, entitled “My World and Welcome to It” after a 1942 collection of his work, was broadcast on NBC.

It starred William Windom as the Thurber figure. Featuring animated segments in addition to live actors, the show won a 1970 Emmy Award as the year’s best comedy series.

Mr. Windom won an Emmy as well. He went on to perform Thurber material in a one-man stage show, including at the Bermuda Festival.

Read More About

Category: All, Entertainment, History

My grandmother had an autographed book of cartoon characters penned by James Thurber. My grandmother met him when she worked in the hotel industry. She died years ago and the book went missing. I have searched high and low for it…no luck.