National Trust Talk On Bermuda Quarrying

A Bermuda historian once summed up the island’s quarrying tradition as well as anyone when he said “it is a great advantage when you can dig your house out of your own backyard.”

And last Sunday [Apr. 27] the Bermuda National Trust hosted an open air “Trust Talk” at the new Vesey Nature Reserve in Southampton on the subject of one of the island’s oldest building traditions.

Presented by Larry Mills, the dramatic 25-foot tall rock cuts of the Skroggins Quarry provided the perfect setting to explain the history and techniques of quarrying used in Bermuda.

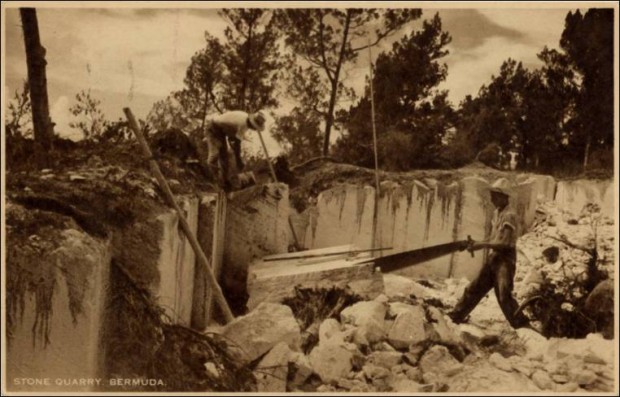

Mr. Mills explained how labour-intensive and skillful the work was between the 17th and early 20th centuries: quarry men [seen below in a photo dating from the early 1900s] had to identity the perfect location for excellent limestone, cut blocks by hand with long chisels and six-foot long saws.

“They were balancing on tall ladders to get to the final cuts, had to endure excessive heat while working, were constantly covered in dust and in danger of being seriously injured by falling rocks and blocks,” said a Trust spokesman.

The presentation was enhanced with facts and anecdotes by Fred Phillips and Robert Simons who both have worked in Bermuda’s quarries before the use of motorised tools and National Museum of Bermuda director Dr. Edward Harris stressed the importance of the quarries for Bermuda’s fortifications.

Kevin Horsfield spoke about his grandfather’s invention of the stone cutting saw and its impact on the quarrying industry.

Bermuda’s stone has been used from the early days of settlement for building, first for forts and public buildings and later for houses.

Larry Mills and Kevin Horsefield at the “Trust Talk” on Bermuda quarrying techniques

“Walls were made of soft stone sawn into building blocks with longiron handsaws,” says an official history of the Bermuda quarrying tradition compiled by the Planning Department. ”Then, it was common for blocks to be obtained from the site where a building was to be erected.

“Part of a sloping hillside was cut away and a house put in the space created, which formed the cellar. Many old properties have quarry “starts” which show that additional quarrying was also done on site.”

To begin the quarrying, stonecutters would try and determine how the stone was bedded. They would select a suitable starting point and chisel and rake out a three inch trough around the first stone to be cut.

This first stone, called the head stone or key block, was like the first piece of a pie. Getting it out was the hardest part of the job. The rest of the blocks were much easier to remove. The bottom of the blocks were riven with hardwood wedges or undermined in a wedge shape with chisels, and pried loose.

They were allowed to fall to the ground where they landed on a bed of scrap stones, called “jacks” or “slipes”.

“These absorbed the impact of the fall. The blocks, which were as large as 12 to 15 feet high, were then sawn or riven along the grain into building stones of different sizes,” says the Planning Department history. “Sound stone with a very even grain was reserved for roofing slates. This was selected by eye or by tapping with the knuckles to hear what kind of ring it had. Inferior stone and offcuts were used as slipes or for drystone walls. The sand that was a by-product of sawing stone was also used. There was never any waste.”

Bermuda’s first stonecutters were often slaves or indentured labourers.

After Emancipation, the trade was often in the hands of working immigrants, both West Indian and Portuguese.

In the 19th and 20 centuries, skilled masons with the knowledge to lay newly cut Bermuda stone were mostly members of the black community.

Mortars are used to bond together blocks of stone and to help form a level bed from which to build.

Mortars were based on lime, which may be the single most important element in our traditional building. Lime was easily available in Bermuda though it was costly because of the fuel and the labour it required.

It was made by burning hard stone in a limekiln.

– Photographs courtesy of the Bermuda National Trust

Read More About

Category: All, Environment, History

Kevin Horsefield: Please email me—the last (only) time we saw each other was hitchiking opposite directions in Halls Creek, Australia–hanging out at the only gas station for 300 + miles or so. Was that you? Reading about your fame here in Fullerton, California.