Washington Irving On Bermuda’s “Three Kings”

The tale of the “Three Kings of Bermuda” — a trio of survivors from the “Sea Venture” wreck left behind on the island after the final departure of the “Patience” for England in 1610 and the arrival of the first permanent settlers in 1612 — has inspired archaeologists from the University of Rochester to search for their campsite on Smith’s Island.

The tale of the “Three Kings of Bermuda” — a trio of survivors from the “Sea Venture” wreck left behind on the island after the final departure of the “Patience” for England in 1610 and the arrival of the first permanent settlers in 1612 — has inspired archaeologists from the University of Rochester to search for their campsite on Smith’s Island.

And more than 170 years ago the story of Edward Chard, Robert Waters and Christopher Carter also inspired American writer Washington Irving to speculate on a possible connection between the “three fugitive vagabonds” and William Shakespeare’s Bermuda-influenced play “The Tempest.”

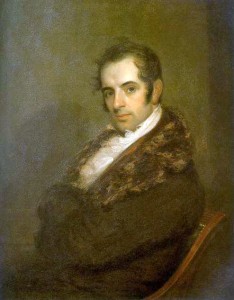

Washington Irving [1783–1859] was an American author, essayist, biographer, historian and diplomat.

Best known his short stories “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle”, his historical works include biographies of George Washington, Oliver Goldsmith and Muhammad along with several histories of 15th-century Spain.

Irving [seen here in a 19th century portrait] continued to publish regularly — and almost always successfully — throughout his life, and completed a five-volume biography of George Washington just eight months before his death, at age 76, in Tarrytown, New York.

Irving — who along with James Fenimore Cooper was among the first American writers to earn widespread eacclaim in Europe — visited Bermuda once and became fascinated by the island because he could “trace in [its] early history, and in the superstitious notions connected with them, some of the elements of Shakespeare’s wild and beautiful drama ‘The Tempest’ …”

The story of the “Three Kings” began in 1610 when the “Sea Venture’s” Sir George Somers returned to the island from Jamestown in the Bermuda-built “Patience” to ship additional provisions to the starving survivors of the Virginia settlement.

He died here on November 9, 1610.

In the aftermath of the “Sea Venture” wreck, Admiral Sir George Somers’ mapped Bermuda

Rather than return to Virginia with much-needed supplies, Sir George’s nephew Matthew Somers oped to sail the “Patience” to England to inform the Virginia Company — financiers of the Jamestown settlement — of Bermuda’s potential as a new colony.

Carter and Chard, who had earlier refused to accompany Sir George to Virginia when the “Patience” and “Deliverance” embarked for Jamestown, now balked at returning to England with Matthew Somers. They elected to stay behind in Bermuda, joined by a third man, Waters.

As Bermuda historian Carveth Wells once said, all went well until a serpent in the form of greed entered the paradise of Bermuda: ” … One day they found a large block of ambergris that weighed over eighty pounds. Knowing the enormous value of their find, they divided it into three parts and suddenly became rich men.

“… They probably started thinking about their ancestors and family trees, discussions concerning which led to quarrels and finally to a duel between Chard and Waters. Carter, however, being possessed of a sense of humor, hid their weapons and the duel resolved itself into a contest of sulkiness.

“After [20 months] of wealth with no place to go, they decided to build a boat and set sail with their ambergris to England, but just as they were on the point of sailing, a vessel arrived with the new Governor on board.”

Washington Irving claimed to see parallels between the story on the men who ”remained in possession of the island of Bermuda on the departure of their comrades and in their squabbles about supremacy on the finding of their treasure” and characters and incidents in “The Tempest.”

His full essay “The Three Kings Of Bermuda & Their Treasure Of Ambergris” — first published in 1840 — is reproduced below:

Washington Irving’s “The Three Kings Of Bermuda:

At the time that Sir George Somers was preparing to launch his cedar-built bark, and sail for Virginia, there were three culprits among his men, who had been guilty of capital offences. One of them was shot; the others, named Christopher Carter and Edward Waters, escaped. Waters, indeed, made a very narrow escape, for he had actually been tied to a tree to be executed, but cut the rope with a knife, which he had concealed about his person, and fled to the woods, where he was joined by Carter. These two worthies kept themselves concealed in the secret parts of the island, until the departure of the two vessels. When Sir George Somers revisited the island, in quest of supplies for the Virginia colony, these culprits hovered about the landing-place, and succeeded in persuading another seaman, named Edward Chard, to join them, giving him the most seductive pictures of the ease and abundance in which they revelled.

When the bark that bore Sir George’s body to England had faded from the watery horizon, these three vagabonds walked forth in their majesty and might, the lords and sole inhabitants of these islands. For a time their little commonwealth went on prosperously and happily. They built a house, sowed corn, and the seeds of various fruits; and having plenty of hogs, wild fowl, and fish of all kinds, with turtle in abundance, carried on their tripartite sovereignty with great harmony and much feasting. All kingdoms, however, are doomed to revolution, convulsion, or decay; and so it fared with the empire of the three kings of Bermuda, albeit they were monarchs without subjects. In an evil hour, in their search after turtle, among the fissures of the rocks, they came upon a great treasure of ambergris, which had been cast on shore by the ocean. Beside a number of pieces of smaller dimensions, there was one great mass, the largest that had ever been known, weighing eighty pounds, and which of itself, according to the market value of ambergris in those days, was worth about nine or ten thousand pounds!

From that moment, the happiness and harmony of the three kings of Bermuda were gone for ever. While poor devils, with nothing to share but the common blessings of the island, which administered to present enjoyment, but had nothing of convertible value, they were loving and united: but here was actual wealth, which would make them rich men, whenever they could transport it to a market.

Adieu the delights of the island! They now became flat and insipid. Each pictured to himself the consequence he might now aspire to, in civilized life, could he once get there with this mass of ambergris. No longer a poor Jack Tar, frolicking in the low taverns of Wapping, he might roll through London in his coach, and perchance arrive, like Whittington, at the dignity of Lord Mayor.

With riches came envy and covetousness. Each was now for assuming the supreme power, and getting the monopoly of the ambergris. A civil war at length broke out: Chard and Waters defied each other to mortal combat, and the kingdom of the Bermudas was on the point of being deluged with royal blood. Fortunately, Carter took no part in the bloody feud. Ambition might have made him view it with secret exultation; for if either or both of his brother potentates were slain in the conflict, he would be a gainer in purse and ambergris. But he dreaded to be left alone in this uninhabited island, and to find himself the monarch of a solitude: so he secretly purloined and hid the weapons of the belligerent rivals, who, having no means of carrying on the war, gradually cooled down into a sullen armistice.

The arrival of Governor More, with an overpowering force of sixty men, put an end to the empire. He took possession of the kingdom, in the name of the Somer Island Company, and forthwith proceeded to make a settlement. The three kings tacitly relinquished their sway, but stood up stoutly for their treasure. It was determined, however, that they had been fitted out at the expense, and employed in the service, of the Virginia Company; that they had found the ambergis while in the service of that company, and on that company’s land; that the ambergis, therefore, belonged to that company, or rather to the Somer Island Company, in consequence of their recent purchase of the island, and all their appurtenances. Having thus legally established their right, and being moreover able to back it by might, the company laid the lion’s paw upon the spoil; and nothing more remains on historic record of the Three Kings of Bermuda, and their treasure of ambergris.

* * * * *

The reader will now determine whether I am more extravagant than most of the commentators on Shakespeare, in my surmise that the story of Sir George Somers’ shipwreck, and the subsequent occurrences that took place on the uninhabited island, may have furnished the bard with some of the elements of his drama of the Tempest. The tidings of the shipwreck, and of the incidents connected with it, reached England not long before the production of this drama, and made a great sensation there. A narrative of the whole matter, from which most of the foregoing particulars are extracted, was published at the time in London, in a pamphlet form, and could not fail to be eagerly perused by Shakespeare, and to make a vivid impression on his fancy. His expression, in the “Tempest”, of “the still vext Bermoothes,” accords exactly with the storm-beaten character of those islands. The enchantments, too, with which he has clothed the island of Prospero, may they not be traced to the wild and superstitious notions entertained about the Bermudas? I have already cited two passages from a pamphlet published at the time, showing that they were esteemed “a most prodigious and inchanted place,” and the “habitation of divells;” and another pamphlet, published shortly afterward, observes: “And whereas it is reported that this land of the Barmudas, with the islands about, [which are many, at least a hundred] are inchanted and kept with evil and wicked spirits, it is a most idle and false report.” [Footnote: "Newes from the Barmudas;" 1612.]

The description, too, given in the same pamphlets, of the real beauty and fertility of the Bermudas, and of their serene and happy climate, so opposite to the dangerous and inhospitable character with which they had been stigmatized, accords with the eulogium of Sebastian on the island of Prospero:

“Though this island seem to be desert, uninhabitable, and almost inaccessible, it must needs be of subtle, tender, and delicate temperance. The air breathes upon us here most sweetly. Here is every thing advantageous to life. How lush and lusty the grass looks! how green!”

I think too, in the exulting consciousness of ease, security, and abundance felt by the late tempest-tossed mariners, while revelling in the plenteousness of the island, and their inclination to remain there, released from the labors, the cares, and the artificial restraints of civilized life, I can see something of the golden commonwealth of honest Gonzalo:

“Had I plantation of this isle, my lord,

And were the king of it, what would I do?

I’ the commonwealth I would by contraries

Execute all things: for no kind of traffic

Would I admit; no name of magistrate;

Letters should not be known; riches, poverty,

And use of service, none; contract, succession,

Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none:

No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil:

No occupation; all men idle, all.All things in common, nature should produce,

Without sweat or endeavor: Treason, felony,

Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine,

Would I not have; but nature should bring forth,

Of its own kind, all foizon, all abundance,

To feed my innocent people.”But above all, in the three fugitive vagabonds who remained in possession of the island of Bermuda, on the departure of their comrades, and in their squabbles about supremacy, on the finding of their treasure, I see typified Sebastian, Trinculo, and their worthy companion Caliban:

“Trinculo, the king and all our company being drowned,

we will inherit here.”“Monster, I will kill this man; his daughter and I will be king and queen, (save our graces!) and Trinculo and thyself shall be viceroys.”

I do not mean to hold up the incidents and characters in the narrative and in the play as parallel, or as being strikingly similar: neither would I insinuate that the narrative suggested the play; I would only suppose that Shakespeare, being occupied about that time on the drama of “The Tempest”, the main story of which, I believe, is of Italian origin, had many of the fanciful ideas of it suggested to his mind by the shipwreck of Sir George Somers on the “still vext Bermothes,” and by the popular superstitions connected with these islands, and suddenly put in circulation by that event.

-

Read More About

Category: All, Entertainment, History