Bermuda: ‘Unsung Heroes’ of Space Race

Bermuda’s NASA tracking station, at the end of Mercury Road on Cooper’s Island, adjacent to Clearwater Park, lies abandoned now, most of the facilities dismantled. But Cooper’s Island still retains signs from its heyday which began with the US/Soviet “space race” and ended after a 1997 space shuttle innovation rendered the station unnecessary.

Bermuda’s NASA tracking station, at the end of Mercury Road on Cooper’s Island, adjacent to Clearwater Park, lies abandoned now, most of the facilities dismantled. But Cooper’s Island still retains signs from its heyday which began with the US/Soviet “space race” and ended after a 1997 space shuttle innovation rendered the station unnecessary.

Located on a 77-acre rock-coral shelf just off of Saint David’s Island on the northern shores, the main station was an eastward extension of Kindley Air Force Base, managed by the US Air Force. Its use dated back to a World War II agreement between US President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. A smaller site was in Town Hill on the main island.

At the height of the space race, 6,000 men and women operated the US National Aeronautics & Space Agency’s Spaceflight Tracking and Data Network (STDN) at some two dozen locations across five continents. STDN was an intricate system of ground stations, computer facilities, and communication centers that supported everything from the launch of communications satellites to the astronauts’ journeys.

STDN began by tracking the former Soviet Union’s Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite, and played a crucial role in every near-earth space mission for the next 40 years. STDN received the first television images from space, tracked Apollo astronauts to the Moon and back, and acquired data for earth science.

Those who comprised STDN, the so-called “invisible network,” have never been responsible for the compromise of a NASA mission. They are considered by many to be “the unsung heroes of the space programme.”

In March 1961, less than two months before Alan Shepard’s scheduled suborbital flight, Washington DC, reached an agreement with the UK to operate a tracking station on Bermuda.

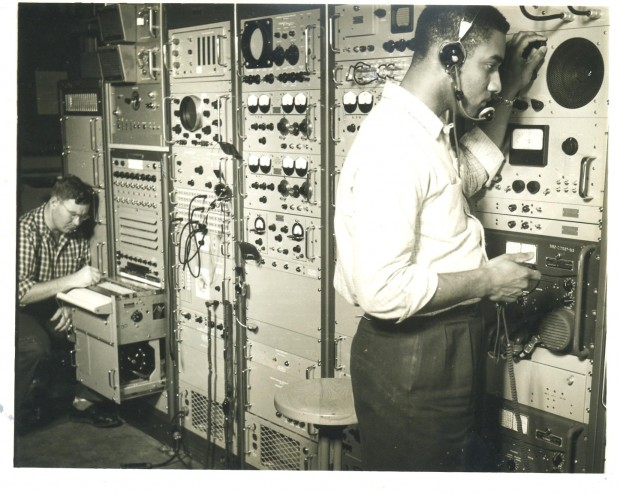

The station cost $5 million to build in 1961. For fiscal and diplomatic reasons, local workers were used as much as possible to build the station [pictured below], and NASA employed 60 contractors and 20 Bermudians to operate it.

Bermuda was one of NASA’s first stations built on foreign soil and was also one of the most critical. With the exception of Cape Canaveral, it was the most complex and important of the 15 Mercury Space Flight Network (MSFN) ground stations. The Mercury Atlas flight path was almost directly over the island, which enabled a brief but essential 25-second window to track and make decisions about its status as it ascended into orbit.

The vital determination to abort or continue a flight was known as “Go/No Go.” During the launch of an Atlas rocket — a US Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile used to launch the Mercury astronauts and NASA’s early large satellites— a decision to continue or abort had to be made in only a 30- to 120-second window after the rocket’s main engine had cut off.

The failure rate of the Atlas booster in those early days was very high – about 50 percent – so aborted missions were common. The Bermuda station was established to keep an eye on every Cape Canaveral launch and the first critical phases of the flight downrange, making it a key station during the launch phase of any mission. The control centre at Bermuda provided reliable communications and controls in the event that it became necessary to make abort decisions.

Many mathematical and trajectory experts believed such a ‘”short arc” solution would be impossible, but data analysis — some of it generated by the Bermuda tracking station – determined that, even with such a small timeframe, a spacecraft could be turned around and its retrorockets fired so that it could reenter in the Atlantic recovery area before reaching its point of impact on the African coast.

When construction of the station began in April 1961, a headline in “The Royal Gazette” announced that “Bermuda Tracking Station Has Vital Part to Play in First Manned US Spaceflight.” The article informed readers that “an order from here could bring it down.”

During Project Mercury, NASA’s first man-in-space programme, the network was not well-centralised and communication was done by sometimes-unreliable teletype, so flight controllers were dispatched to most of the primary tracking stations in order to maintain immediate contact with the spacecraft from the ground. Astronauts also acted as capsule communicators (known as Capcoms) at various sites.

Donald K. (Deke) Slayton, head of Flight Crew Operations at Houston’s Manned Spacecraft Center, was said to have assigned astronauts to Bermuda (as well as sites in Hawaii, California, and Australia) to give them some much-needed rest and relaxation in beautiful places.

Prior to John Glenn’s first Mercury orbital mission, the Bermuda station played a key role in the flight of space chimp Enos and the “apeonaut” was brought to the island after he returned to earth.

This 1961 mission was to qualify the Mercury spacecraft and all its systems during orbit and re-entry. The spacecraft and Enos splashed down safely around 200 miles off Bermuda a two-orbit flight.

Originally scheduled for three orbits, the spacecraft was returned to earth after two orbits due to the failure of a roll reaction jet and to the overheating of an inverter in the electrical system. Enos’ Mercury capsule was picked up by the USS “Stormes” and brought to Kindley Air Force Base. The chimpanzee’s medical debriefing at Bermuda showed he had no ill effects from his space ride.

And on Project Mercury’s very last flight in May, 1963 [the launch is pictured at top], STDN reported 15 incidents of radio interference In Bermuda, a Voice of America broadcast was heard as well as a Greenville, North Carolina, amateur radio operator. Department of Defense frequency controllers contacted the offending operator and cleared the NASA channels, but several times amateur radio operators successfully contacted astronaut Gordon Cooper, though he was directed by Mercury Control Center not to respond to them.

In 1963, to prepare for sending astronauts into space, an ocean floor cable capable of carrying 2,000 bits-per-second of digital information was laid to connect the new station on Bermuda with Cape Canaveral. This link continued to serve the Bermuda Station well into the space shuttle era.

The Bermuda station was overhauled in preparation for the Apollo lunar landing programme. As it had been on Mercury and the later Gemini programmes, Bermuda would be an essential station immediately after launch. As the first station to electronically see the rocket, operators could observe most of the second and third stage burns at high elevation angles.

Bermuda monitored the ascent of the Saturn V into orbit and provided the critical “Go/No Go” data to Mission Control for flight continuation or a decision to abort the mission.

In March 1965, a request was submitted for a $1.6 million consolidation and upgrade to the MSFN facility on Bermuda so it could meet the combined requirements for projects Gemini and Apollo.

All of the various telemetry facilities scattered around in pre-fabricated metal structures and trailers on Town Hill and Cooper’s Island were to be consolidated. The original facilities also were corroded by years of sea salt and moisture. An air conditioned, 1,100-square meter Operations Building was built and a 300-square meter Generator Building housed the diesel generator.

Next to the USB antenna, a small building contained the hydro-mechanical equipment that pointed the massive antenna. Concrete foundations were dug for the dish and the collimation tower. Extensive cabling was installed, and a microwave terminal was relocated. 30 percent more maintenance and administration staff was added as well as 26 additional technicians as the site was ramped up to support Gemini and Apollo missions. When the Cooper’s Island upgrade was completed, NASA dismantled the Town Hill telemetry site.

Shuttle flights on easterly trajectories went all the way into orbit on their backs. In November 1997, Columbia, the shuttle programme’s 88th flight, was the first to roll the entire stack from its usual belly-up to a belly-down position in a 40-second maneuver six minutes after liftoff. Known as a Roll-to-Heads-Up (RTHU) maneuver, it’s performed prior to main engine cutoff so that communication with the contemporary space-based Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS) can be established some two and a half minutes sooner. Such a maneuver previously had been used only if Mission Control declared an emergency landing due to a failed main engine or the loss of cabin pressure during the crew’s ascent into orbit.

This innovation meant that the Bermuda station was no longer necessary for the success of NASA launches. The decision to close the site was ultimately a financial one, as it saved NASA $5 million a year; coincidently the same amount required to build the station in 1961.

With Bermuda closed, Merritt Island/Ponce de Leon in Florida became the only source of tracking data for the first seven minutes of each space shuttle launch.

The gradual phase-out of the Bermuda station — completed in 2001 – signalled the end of the era of the worldwide network of spaceflight tracking stations. Bermuda had supported every human spaceflight that NASA had flown, making the critical “Go/No-Go” call on 118 missions.

Read More About

Comments (6)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Articles that link to this one:

- NASA Remembers Apollo 1 Crew | Bernews.com | January 28, 2013

- Photos: NASA Images Of Bermuda From Space | Bernews.com | January 27, 2014

- Photos: NASA Research Aircraft In Bermuda | Bernews.com | June 15, 2014

If anyone has been to Coopers Island lately there is not much left of NASA to see. The dishes went years ago & the main building, as pictured, has been torn down too.

The construction dates quoted are misleading, construction of the station began in 1959 and was basically completed by October 1960. The construction provided part-time jobs for many Airmen and full-time jobs for many locals. The March 1961 formal agreement with the UK to operate a tracking station on Bermuda was only a formality at the time of the official opening, the station was completed and operational by March 1961. To bad someone in Tourism didn’t think about the possibilty of turning the site into a tourist attraction.

I was there last summer and went to take pictures. Well I got a few good shots of waves breaking over the reefs. Yes, it would have been a nice tourist. Is there a blog where ex-NASA/Subcontractor folks to get together? Either, Bermuda tracking, other sites, Greenbelt, etc.

lcmello1@att.net