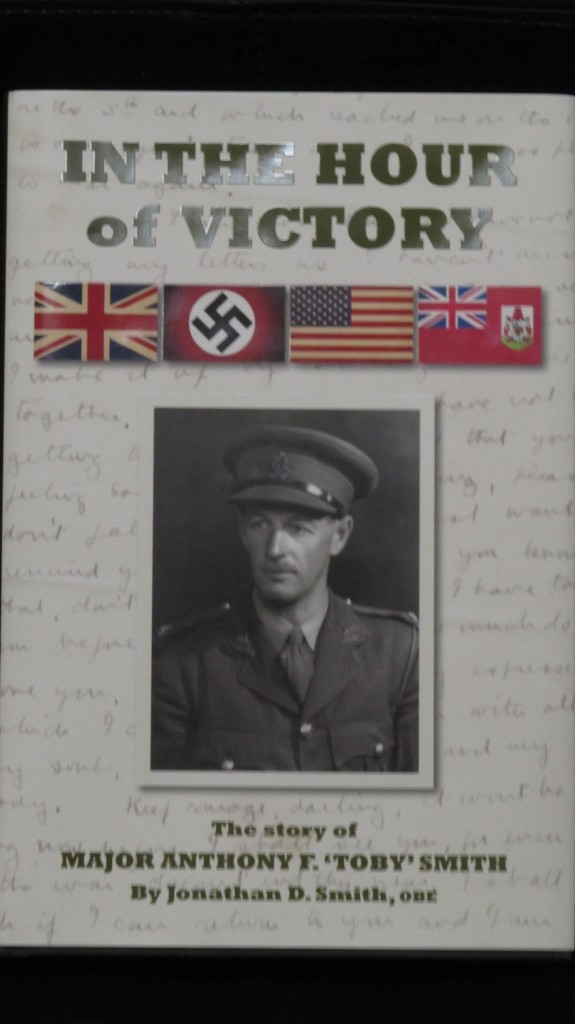

Book Review: ‘In The Hour Of Victory’

[Written by Jonathan Land Evans]

In his 2011 book “In The Hour Of Victory”, Senator Jonathan D. Smith has presented an absorbing transcription of wartime letters sent home by his grandfather, the Second World War Bermudian soldier Major Anthony F. [Toby] Smith — mostly to his wife, Faith, during the course of his military service in England and — very briefly, just prior to his being killed in combat — in North-Western Europe.

Together with Jonathan Smith’s own not-very-extensive but helpful background notes, the letters conjure-up a Bermudian wartime experience that was noteworthy and even highly exemplary — though not, as we shall see, a wartime experience that was beyond criticism.

Although set against a backdrop of dramatic world events, and infused with Toby Smith’s high sense of patriotism and duty, the tenor of the letters is predominantly domestic and administrative. Of no great historical consequence, the letters nonetheless offer the modern reader an intimate and often touching glimpse of real life during the war. They usefully remind us that not all wartime service was heroic in the clichéd, cinematic action-hero sense. Importantly, they bring home — literally as well as figuratively — the wrenching personal costs of war, in terms of relationships strained or violently broken; of family histories whose paths were poignantly and forever affected by the toll of assorted human miseries that war imposes.

During his prolonged years of service overseas, the writer of these wartime letters was often frustrated, embittered, and melancholic, but ultimately he always took satisfaction in doing his best, both militarily and matrimonially, whilst always also drawing comfort from his unshakeable beliefs in God and in England. There is much poignancy and pathos in the letters. Despite his eagerness for battle against the Axis forces, Captain Smith [who came to hold the temporary rank of Major] saw very little combat during his more than four years of wartime service in the regular British Army. Indeed, it was his misfortune to be killed in what was evidently his very first encounter with the enemy, in Holland in October 1944.

As a quite junior officer, whose duties were chiefly as a company-commander of Lincolnshire Regiment troops deployed in England’s East Anglia, and, for a time, as an instructor of officer cadets, Toby Smith was not one of those military officers whose deeds and decisions influenced the course of the Second World War in any grandiose or even in any direct way, although he no doubt exerted a very creditable influence on those platoon-leaders and other young officers who benefited from his evident professionalism, and from his passion for soldiering in defence of freedom.

As its raw material is as much marital as martial, the book is perhaps more interesting psychologically than historically. Toby’s letters home are mostly personal and mundane in nature, and although he was evidently kept very busy with his various military duties, the wartime security protocols and official censorship in operation at the time ordained that the letters tell us relatively little of hard-edged military matters, and they are by no means the stuff of high drama.

They are also unfortunately one-sided in nature: for in Toby’s letters home we sometimes get echoes of his wife’s letters to him, but her letters are not reproduced in the book [perhaps because they were not available to Jonathan Smith, although he does not elucidate this shortcoming].

While frustrating, such one-sidedness is also, in its way, a rewarding challenge to the reader, who, denied sight of the wife’s half of this prolonged long-distance matrimonial dialogue, must to some extent infer and intuit his or her way though Toby’s letters in order to appreciate the totality of the couple’s wartime experiences.

The book does cast a degree of light on the broader history of Bermuda and Bermudians in the Second World War, and also on the Home Front in England, with all its tedium, its quotidian worries and cheers, and the banal and slightly surreal quasi-normalcy of life carrying on, enlivened by letters and periodicals from home and by occasional air-raids, as well as by the BBC radio news. To me, however, the book is of interest chiefly for its revealed insights into the mind of its subject, and rather less so as a contemporaneous historical memoir, or as a history book in the conventional sense [although Jonathan Smith’s various notes and commentaries do help to make the book useful as history too]. Reduced to its essence, “In the Hour of Victory” is an intimate, poignant and fragmentary record of feelings and of family relations, evoking for the reader the fleeting and fragile nature of human happiness, and capturing the various preoccupations of rather ordinary people coping as best they could with not-so-ordinary circumstances.

The character of Toby, as it gradually reveals itself to us through his letters to his wife, is of an appealing complexity that imparts strong human interest to an otherwise mundane and historically inconsequential chronicle — rather more so, indeed, than is the case with the more elaborately literary and historical kinds of soldierly memoirs usually written after the end of hostilities], where it is the selectively-remembered adventures and misadventures of the battlefield, the camaraderie and black humour of the troops, and the grand sweep of events, that are most in focus.

That very mundaneness, and especially also the tenderness, of Toby’s frequent letters impart their own sad but special charm to the book, whilst his private outbursts about various pet hates [most notably, some of his fellow Bermudians] add spice to the general blandness [from a letter dated November, 14, 1940: “I wish some of the money-grubbers there [Bermuda] could get a few bombs on their dear old shops and precious belongings and have a few planes zooming down out of the sky in the dawn with machine guns blasting at them and then [maybe?] they might realise that their grasping, dirty profiteering doesn’t count for much … It makes me boil when I think of men like Trott, Spurling, Vesey and your Coxes and whatnots simply coining money while a nice, safe distance in this war, and the last thing they talk of, freedom, while their medieval and plutocratic “ideals” still live on and they amass fortunes.”]

Front Street, Bermuda, 1941: While Toby Smith Was Serving Overseas In The Military, The Island’s Elite Fêted The Visiting Magda Lupesca, Mistress of Romania’s King

Through no fault of his own — in fact, very much against his own wishes — Toby’s wartime career took the form mostly of worthy diligence far away from the battlefronts. For the most part, his experiences took place in the comparative safety of England’s East Anglia –- being trained himself, and then training other, more junior, British Army soldiers or Home Guard volunteers –- rather than taking the form of dramatic exploits and collective adventures on foreign battlefields. Toby met his death in a brief probing action against occupying German forces in Holland, not long after his arrival on the North-Western European front-line in the early autumn of 1944.

Of course, that sudden and tragic finale is not encompassed in Toby’s own letters. Rather, it is left to others –- in condolence letters and later recollections that are helpfully appended to the main body of the book — to furnish such facts as are known of his final moments, and to extol him as the well-meaning, brave, diligent, and family-loving soldier that he so evidently was.

The psychological tension that successfully holds together this fragmentary and otherwise not especially significant collection of correspondence stems from Toby’s fateful decision soon after the outbreak of war, whilst still living in peaceful Bermuda as an officer of the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps, to volunteer for immediate service overseas in the regular British Army.

In this regard, it should be borne in mind [for it is very much the crux of the book] that the outbreak of war in the late-summer of 1939 found Toby married since 1933 to an American woman, Faith, with whom he had four young children — soon to be five, although sadly he never saw the youngest of them. Prior to the outbreak of war, he had been the manager of the Horizons cottage-colony in Paget — a job he evidently disliked and was glad to escape.

A fundamentally good man but somewhat insecure and, in his correspondence with his wife, rather controlling, Toby clearly paid a high price for his fateful decision to leave Bermuda and join more directly in the good fight against Hitler: a price that must be reckoned not just in terms of Toby’s eventual sudden death in action, but in several years of acute loneliness, frustration, and wearisome toil leading up to that final moment.

Indeed, Toby’s letters become full of sentimentality [one that perhaps gave more solace to he himself than to the recipient of the letters, but which certainly renders his eventual death all the more poignant]. As the years of painful separation elapsed, Toby fantasised so often about being reunited with Faith and the children, and he invoked so many pious and fervent prayers to that end, that it seems almost indecent that his fondest hopes should finally have been so utterly and comprehensively dashed.

To read this collection of letters with the empathy and objectiveness they deserve is to be emotionally drained by them.

One minor objection I have is that Jonathan Smith decided to edit “most” of Toby’s letters, apparently to remove “repetitive” sections from them. It would probably have been wiser for him to have included everything, rather than presuming silently to improve upon what was actually written by Toby. It seems improbable that the omitted passages would have been so very lengthy or out-of-keeping with the general tenor of the book.

Better, surely, to have let Toby’s own very human voice carry comprehensively through, repetitions included. Conceivably such omitted passages might have added to our understanding of, and admiration for, that brave, well-meaning and sadly frustrated warrior, Anthony F. [Toby] Smith [1907-1944], whose memory and example are otherwise so well preserved in Jonathan Smith’s absorbing and worthwhile book.

Bermudian Jonathan Land Evans is a lawyer, writer and historian, with an academic background in international relations and international economics; educated at Saltus Grammar School, the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, the School of Advanced International Studies [SAIS] in Washington DC, and University College, London University.

Congratulations Mr.Smith on your book, well done!!

big up