Clyde Roper’s Quest For The Giant Squid

One of the Bermuda Underwater Exploration Institute’s most eminent international advisors, Dr. Clyde Roper has been called the Ahab of the squid world.

One of the Bermuda Underwater Exploration Institute’s most eminent international advisors, Dr. Clyde Roper has been called the Ahab of the squid world.

Like the whale-obsessed captain of the “Pequod” in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel “Moby-Dick”, Dr. Roper’s pursuit of another legendary leviathan has taken him around the world several times: onto the decks of storm-tossed ships, into submersibles suspended deep under the ocean’s surface, onto remote beaches, and back to his laboratory at Washingfton’s Smithsonian Institution Museum of Natural History to examine battered and bruised specimens of the elusive Architeuthis in his lifelong quest to unravel its secrets.

“Architeuthis is, of course, the giant squid—60-feet long with unblinking eyes the size of a human head, a parrot-like beak nestled within its eight arms and a pair of grasping tentacles that it may or may not use in its titanic battles with the sperm whale, the bane of Ahab’s existence,” said a Smithsonian profile of Dr. Roper.

“For centuries, the giant squid was thought to be mythical, a figment of the imaginations of sailors too long at sea. Their reality became accepted in the 1870s, when several were found dead or dying off Newfoundland. Parts of them have been found in the stomachs of whales and occasionally on the beaches of Bermuda.

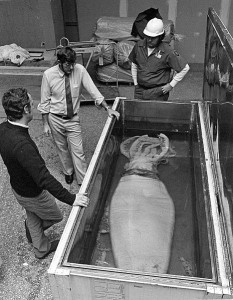

“From such evidence, scientists like Dr. Roper — pictured here in 1983 with a relatively small specimen being prepared for display at the Smithsonian — determined the giant squid is the world’s largest invertebrate animal. Its body can be up to 13 feet wide. It has eight stout arms and two much longer and thinner tentacles.”

Altogether, scientists estimate one of these squid can weigh a ton and, including tentacles, extend 65 feet. Sightings of giant squid over the centuries are undoubtedly responsible for the vast lore of sea monster tales.

Aristotle called the giant squid “teuthos”. Pliny’s “Natural History” described one with arms “knotted like clubs” 30 feet long and a head as big as a cask. In 1555 the Swedish cleric Olaus Magnus wrote of “monstrous fish” of “horrible forms with huge eyes…One of these Sea-Monsters will drown easily many great ships provided with many strong Marriners.”

Dr. Roper is interviewed in this Discovery Channel giant squid documentary

Other lurid but unsubstantiated stories abounded; one had six French men-of-war and the four British ships that had captured them all being dragged under by a gigantic cuttlefish.

The earliest realistic record of Architeuthis is of an animal beached on Iceland’s shore in 1639. More sightings followed. In the 1850s, Danish zoologist Japetus Steenstrup analysed these accounts, examined some recent specimens, and concluded that the alleged sea monsters were, in fact, nothing more fantastic than giant versions of squid.

But the air of mystery surrounding these animals has never been easily dispelled.

Dr. Roper was born in Massachusetts in 1937 and raised in New Hampshire, where he worked as a lobsterman between the ages of 14 and 21—but his creatures of choice are cephalopods: octopuses, squids, cuttlefishes and the chambered nautiluses. He studied at the University of Miami under Gilbert Voss, who was then the world’s top squid biologist, and he wrote his dissertation on an Antarctic species.

He came to the Smithsonian Institution in 1966 and has yet to leave, unless you count squid-hunting expeditions. When a dead sperm whale came ashore on a beach in Florida in 1964, Roper hacked it open with an ax to retrieve Architeuthis beaks; when a doctoral candidate cooked up a piece of giant squid in 1973, Dr. Roper was among those on the student’s committee who tried to eat it [and found it tasted bitterly of ammonia].

He has written about 150 scientific papers on cephalopod biology, and in 1984, with Mike Sweeney of the Smithsonian and Cornelia Nauen of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, he wrote the definitive volume “Cephalopods of the World” [Dr. Roper even turns up, thinly disguised, as “Herbert Talley, doctor of malacology,” in Peter Benchley’s 1991 novel “Beast”, the tale of a giant squid that terrorises Bermuda].

Dr. Roper speaks to documentarian Errol Morris on “First Person”

Dr. Roper was one of the driving forces behind the Beebe Project, initiated in Bermuda in 1986. Financed primarily by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA}, with additional support from the National Geographic Society, the American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation, the Explorers Club and International Underwater Contractors, an ocean-diving company, scientists used submersibles to scour the seas around Bermuda in search of rare specimens — including the giant squid.

Participants included scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, the University of Maryland, the University of California’s Los Angeles and Santa Barbara campuses and the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution in Florida.

Despite repeated efforts, no giant squid were located during the Bermuda Beebe expeditions.

Dr. Roper’s current title is the Smithsonian’s zoologist emeritusand he remains the world’s foremost authority on Architeuthis even though he has yet to see a living adult.

In 2004, two Japanese researchers took the first known photographs of a giant squid with a remote-controlled camera submerged 3,000 feet beneath the Pacific Ocean.

Then, in 2012, the elusive sea creature was finally filmed in the wild for the first time by a team based in Japan.

2012 footage of giant squid filmed in its natural habitat

The six-week mission was funded by the Japan Broadcasting Commission [NHK] and the US Discovery Channel, and took place last July.

The squid was filmed using a camera system was developed by Edith Widder, a deep-sea explorer and founder of the Ocean Research and Conservation Association in Fort Pierce, Florida.

She thinks that the key to its success was a focus on the squid’s sense of sight. To avoid bright lights that might scare the squid away, the system uses a low-light camera with a dim red light, because few deep-sea animals see light with such a long wavelength.

Dr. Roper said that the encounters answered longstanding questions. For instance, the giant squid was thought to be fairly passive, but the vigorous bait attacks show that it is actually a very strong swimmer and feeder.

“This has gone a long, long way to helping us understand this animal,” said Dr. Roper, “They did just a marvellous job.”

Read More About

Category: All, Environment