49 Yrs Ago: Chimp’s Space Trip Ends in BDA

Enos, NASA’s pioneering space chimp, splashed down off Bermuda 49 years ago today [Nov 29] after orbiting the earth twice and was brought to the island’s US Kindley Air Force Base to recuperate — paving the way for the manned orbital missions of the celebrated Mercury astronauts.

Enos, NASA’s pioneering space chimp, splashed down off Bermuda 49 years ago today [Nov 29] after orbiting the earth twice and was brought to the island’s US Kindley Air Force Base to recuperate — paving the way for the manned orbital missions of the celebrated Mercury astronauts.

Though they arguably were better at their jobs than the astronauts who followed them, the “astro-chimps” of the Mercury space programme have largely been forgotten.

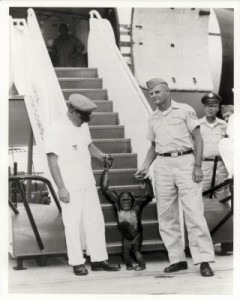

But at the time, “Enos” — who was examined by veterinarians and trainers at the Kindley Air Force Base hospital [pictured at left] and paraded before the international media here — briefly became both a Bermuda and international celebrity.

In the earliest days of the Cold War East/West space race, scientists were concerned about the effects of long periods of weightlessness on humans, so American and Russian scientists began using monkeys, chimps, dogs and other animals to determine if a living organism could be launched into space and return alive and unharmed.

The US sent an expedition to Cameroon, Africa to obtain baby chimps for training. The Cameroon chimps underwent training that their human counterparts couldn’t have completed, such as on dangerous rocket sleds. Chimps were loaded into a chair or capsule, blasted off, then stopped in about two seconds.

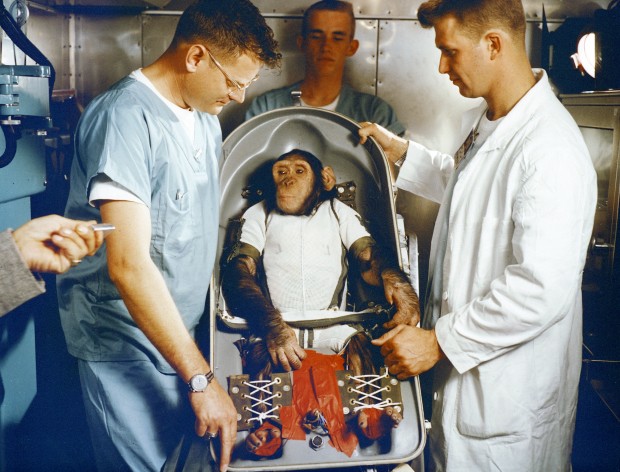

Not every chimp that rode the sled came out alive. In his classic book about the Mercury man-into-space programme, “The Right Stuff”, Tom Wolfe describes the non-stop testing and training of the six “finalist” chimps [pictured below] in gruesome detail, calling the animals “stringy-looking” as a result.

Prior to American first manned orbital mission in 1962, the National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) announced that, “The men in charge of Project Mercury have insisted on orbiting a chimpanzee as a necessary preliminary checkout of the entire Mercury programme before risking a human astronaut.”

Planning for the trial was elaborate. Supporting the mission were 18 tracking stations, including the Cooper’s Island facility in Bermuda. The tracking teams included several Mercury astronauts; Alan Shepard, the first American astronaut into space on a sub-orbital flight in May, 1961, was assigned to Bermuda.

Named right before the flight for the Hebrew word meaning “man,” Enos underwent 1,263 hours of training in psychomotor operations for orbital in-flight performance maneuvers on the Mercury-Atlas rocket.

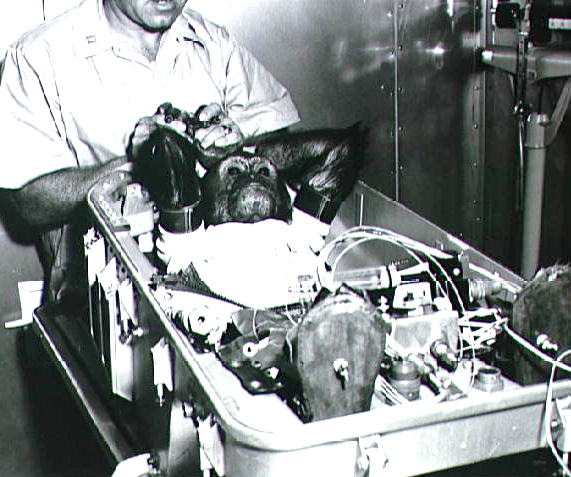

Training included: centrifuge runs, weightless parabolas, heat-chamber and altitude chamber sessions, plus some intelligence tests. Restrained in a pressurised flight couch, with biosensors attached to his body at various points, Enos learned to differentiate between colours and shapes on an instrument panel and was offered right- and left-hand levers to turn off lights.

His intelligence was also tested using a combination of three symbols, two of which matched. He had to pull a lever under the non-matching symbol or receive a shock to the soles of his feet. In most of the tests, correct answers were rewarded with a banana pellet or a drink of water.

Enos was considered the most intelligent of all of the trained NASA chimps, which is why he was chosen for the mission. Captain Jerry Fineg, chief veterinarian for the mission, described Enos as “quite a cool guy and not the performing type at all,” with none of the tendencies of his circus-trained counterparts. Enos was not cuddly and friendly. As one writer speculated, “the electrical shocks could have had something to do with this.”

Enos’ mission was to attempt three orbits of the Earth for the Mercury-Atlas 2 mission. About five hours before the November 29, 1961 launch, the specially constructed primate couch in which Enos was secured was inserted in the spacecraft [pictured below].

He was relaxed during countdown, and all of his bodily functions were normal. Then, a series of delays began, leading some in the control centre to joke that Enos was sabotaging the mission. When the rocket was finally launched, Enos fared well, withstanding a peak of 6.8 g’s during booster-engine acceleration and 7.6 g’s with the rush of the sustainer engine.

The Atlas rocket delivered 367,000 pounds of thrust, nearly five times what pioneering human astronaut Shepard had experienced; Enos was unfazed. At his press conference in Washington, President Kennedy got a round of laughter when he said, “This chimpanzee who is flying in space took off at 10:08. He reports that everything is perfect and working well.”

During the second orbit, the lever for the motor skills test malfunctioned and Enos was shocked rather than rewarded for each correct answer. Nevertheless, he kept pulling the levers, continuing to perform his required operations as he was trained to do, despite the repeated shocks. His suit overheated and the automatic attitude controls malfunctioned, so the capsule repeatedly rolled forty-five degrees before the thrusters would correct it.

Luckily for Enos, given his shocking predicament, mission control decided to end his flight. Three hours and 21 minutes after liftoff — 181 minutes of which he was weightless — Enos re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere and landed in the Atlantic, south of Bermuda. Enos and his spacecraft were hauled aboard the recovery ship USS “Stormes” an hour and 15 minutes after landing.

Engineers scrutinising the capsule found that it had held up well. So had Enos, though he’d ripped through the belly panel of his restraint suit, removing or damaging most of the biomedical sensors from his body, including those that were inserted under his skin. He also ripped out a urinary catheter while he waited in the capsule for pick-up.

But once aboard the destroyer “Stormes”, he ate two oranges and two apples, his first fresh food since he’d been placed on a low-residue pellet diet. The destroyer dropped the chimpanzee astronaut at the Kindley Air Force Base hospital in Bermuda.

But once aboard the destroyer “Stormes”, he ate two oranges and two apples, his first fresh food since he’d been placed on a low-residue pellet diet. The destroyer dropped the chimpanzee astronaut at the Kindley Air Force Base hospital in Bermuda.

The chimp was walked in the corridors and appeared to be in good shape apart from mysteriously high blood pressure, which Wolfe speculates arose from Enos stuffing down his rage at his two years of mistreatment at the hands of humans.

But, at least for a brief time, Enos was hailed as a hero by NASA and the press. His composure at a press conference surprised reporters. Enos was unperturbed by the noise and flashing bulbs, perhaps because of all he’d already endured.

On December 1, Enos was sent from Bermuda to Cape Canaveral [pictured ] for another round of physicals, and a week later he departed for his home station at Holloman, set for retirement. Thanks to Enos, mission managers concluded that a human could withstand orbital missions.

On the date of Enos’ flight, it was announced that Lt. Col. John Glenn would make the first manned orbital mission on February 20, 1962. Glenn orbited the earth in the “Friendship 7″ and became a huge celebrity. In his speech to Congress, he said he was humbled when the president’s daughter, Caroline Kennedy, met him and her first question was “Where’s the monkey?”

Enos’ fame was short-lived as public attention turned to manned orbital flight. Six months after his historic mission, Enos contracted Shigellosis, a rare and potent form of dysentery, and died. His death received little media attention beyond assurances that it had no relation to his space mission.

Comments (2)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Articles that link to this one: