Pilot Darrell: ‘Ability And Steadfastness’

The inscription on his headstone at St. Peter’s Churchyard, St. George’s captures the essence of the man and the high regard in which he was held: “James Darrell, Who died 12th April 1815 aged 66 years. In his public life as a servant of his country he obtained the general approval of his talents and worth. In his private walk as a member of his community his name will long be remembered for his usefulness and integrity. His faith in Christ and his many works of charity eminently proved him a Christian. Gone now to God, his final rest, In his enjoyment to be blest. Gone now to heaven, the seat of bliss His pleasure in perfection is.”

Pilot James (Jemmy) Darrell was a man of many firsts — one of the island’s first King’s Pilots, charged with guiding some of the Royal Navy’s largest and most formidable ships of the line through Bermuda’s treacherous maze of reefs; the first black man to own a house in Bermuda; the first to petition against the laws and prohibitions which circumscribed the liberties of Bermuda’s free people of colour prior to Emancipation.

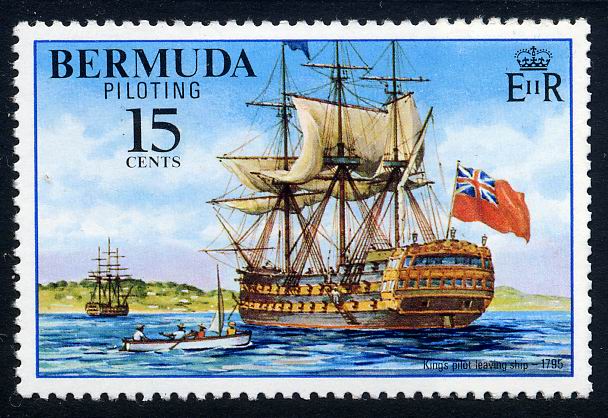

Today [May 19] Minister Kim Wilson launched a new stamp issue on “Piloting in Bermuda” at the Bermuda Post Office while simultaneously opening a new Bermuda Archives exhibit dedicated to Pilot Darrell [pictured below].

Pilot Darrell’s Square in St. George’s is named for James Darrell. He was one of three Bermudian slaves who worked with the Royal Navy’s Lieutenant Thomas Hurd when the first comprehensive survey of the channels and harbours around Bermuda was conducted in the late 18th century.

After the loss of its mainland North American colonies in 1783 Bermuda had, by 1787, assumed a pivotal role in the maintenance of a British colonial empire in the Atlantic.

Bermuda’s location on the trade route between homeland Britain and the remaining 13 British island colonies of the Caribbean was considered critical. The island was further valued by the British as a potential harbour for the relocation of its base of operations for its North American fleet, stationed much further north in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Lieutenant Hurd was sent to Bermuda, to sound existing channels through the reefs and to find new ones prior to the commencement of the British naval build-up on the island. He began his surveys in the late 1780s and completed them in 1792.

It was Lieutenant Hurd’s definitive nine-year survey — conducted in conjunction with the three Bermudian pilots including James Darrell, all of whom had grown up negotiating the island’s treacherous maze of reefs — which proved Bermuda to be a suitable location for a major Royal Navy presence.

Indeed the survey undertaken by Lieutenant Hurd and his Bermudian collaborators was so detailed and accurate that it wasn’t ever published, except much later in 1827 and even then as a much simplified chart, for fear that the information may fall into American hands. The original survey is approximately 17 feet wide by eight feet high when the two halves are put together.

The unrivalled skills and unparalleled courage of Bermudian pilots like Jeremy Darrell were described in a 19th century American newspaper account: “Few white men there are in Bermuda who can take a boat through the reefs … The negro descendants from the old slaves are the pilots who seem to know these reefs from their earliest boyhood.

“They navigate them at night, in change of weather, in fact, at all times.

“… A pilot who was in his gig one night (a pilot gig is a long narrow boat manned by six oarsmen, which can also go under sail), and was wrecked near a stranded three-masted schooner which had gone upon the rocks in a gale the year before. He and the crew succeeded in getting upon the hulk.

“The pilot, not wishing to wait for daylight, decided to swim ashore, a distance of [several] miles, so doffing his clothes he started. He had gone not far before a shark brushed near him, and, according to his story, swam by his side until he encountered the breakers near the atolls that defend the shore.

“In witness of the truth of the pilot’s story. his right side was bereft of its skin to a certain extent, which he explained was the result of rubbing against the shark’s sandpaper skin. When asked if he was afraid, the pilot replied, ‘No, it was rather company for him’ …”

In May 1795, James Darrell piloted British Admiral George Murray’s ship, the 74-gun HMS “Resolution”, through the Narrows Channel into the newly charted Murray’s Anchorage. The channel’s reefs had long been considered a hazard to navigation, but James Darrell guided the great warship safely into the protected anchorage later named after Admiral Murray.

Pilot Darrell guiding HMS “Resolution” through the Narrows Cut

That same year he, along with fellow slave Jacob Pitcarn, was appointed on of Bermuda’s first King’s pilots — their chief duty guiding Royal Navy vessels through the reefs as the British began developing the island as a major military base in earnest.

Admiral Murray was so impressed with James Darrell’s skill that he recommended to Bermuda Governor James Craufurd that Pilot Darrell be granted his freedom.

Describing him as having “great merit for his ability and steadfastedness”, James Darrell was owned by Frances Darrell of St. George’s. But when her died, James Darrell was purchased by the Governor who granted him his freedom in accordance with Admiral Murray’s request.

Pilot James Darrell became a free man in March 1796 at the age of 47 years, and went on to become the first black Bermudian man to purchase a house on the island. The property, renovated in 1992, still stands at Pilot Darrell’s Square and is owned by his descendents.

In the early 1800s he organised a series of petitions sent to London protesting laws passed by Bermuda’s legislature to restrict both the civil liberties and professional opportunities of the island’s free people of colour.

In one such appeal, he said free blacks might be forced to leave Bermuda and “become wanderers, in some other parts of the World, where they may find refuge” unless the prohibitions were lifted. At least one of the laws — limiting the rights of free blacks to own property – was later rescinded after pressure was applied to the Bermuda assembly by the Admiralty in London.

In April, 2009 an ecumenical service was held at St. Peter’s during Bermuda’s 400th anniversary celebrations to honour the life and work of Pilot Darrell.

Read More About

Comments (11)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Articles that link to this one:

- 1777: The Battle Of Wreck Hill | Bernews.com | April 8, 2012

- Museum To Host War Of 1812 Conference | Bernews.com | March 15, 2013

- Upcoming: King’s Pilot James Darrell Service | Bernews.com | April 12, 2013

Did pilot Darrel walk on water as well?

You mad huh?

Some thought he could I am sure

Dumb ASS!

*Did pilot Darrel walk on water as well?*

You’re confusing him with the one who the new court house/police station is named after ….. lol

btw , Jemmy’s house is an architectural icon … I can’t stop looking at it .

As an aside, it is regrettable that the Bermuda Government has allowed numerous Royal Navy Buildings in Dockyard to fall into disrepair and dilapidation. One of these derelict buildings could have been used to house this exhibit on Pilot Darrell. Another lost opportunity to retain Bermuda’s maritime history and heritage and a disservice to the future generations of Bermudians!

There are many of us who are members of the Darrell family that were not raised in Bermuda. Some of us have a love for the island because of the stories that were shared around the dining table. We learned to have just as much a sense of ownership and belonging as if we grew up on the island itself.

I feel a sense of connection that is not easy to describe when reading of the accomplishments of “Jemmy” Darrell. It is more than pride or boasting rights. It is about being able to look back at a piece of history that was documented and point to someone that had some level of positive influence in the creation of that history. It is feeling that through that history we have worth. It gives my family and I a sense of belonging and value.

Thank you to all who have worked so hard to formalize this legacy. In a time when much of what we pass on is sensationalized or regretful, your efforts allow me to pass something on that hopefully encourages and inspires my grands to see themselves as having a responsibillity to the future generations and the desire to continue the legacy.

Dear Ena

I am also in a similar position not having been born in Bermuda. My mother is a Darrell and the legacy of my great grandfather is a source of something very special in my life. Jemmy’s son, James Edward was her grandfather and her father was Stanley. I have met a few of my relatives from this very extended family and I am intrigued at the influence he continues to have on his extended family. One day I would like to visit St Peter’s and see Jemmy’s headstone for myself, meet some relatives and see and understand a little more about survival and courage.

Kind regards

Lynette Neil

QLD, Australia