Enduring Legacy Of Bermuda’s Mary Prince

Published exactly 180 years ago, Bermuda slave Mary Prince’s narrative of her life of servitude on the island and in the Caribbean has lost none of its power to shock. Or to inspire understanding and reconciliation among peoples.

Published exactly 180 years ago, Bermuda slave Mary Prince’s narrative of her life of servitude on the island and in the Caribbean has lost none of its power to shock. Or to inspire understanding and reconciliation among peoples.

For Mary Prince’s first-hand account of the atrocities of slavery was not just intended as an indictment of slave owners in Bermuda and other colonies or as an appeal to natural justice among her British readers. Her historic book was also a declaration of our common humanity.

“Oh the horrors of slavery! … the truth ought to be told of it; and what my eyes have seen I think it is my duty to relate,” she said. “I have been a slave — I have felt what a slave feels, and I know what a slave knows; and I would have all the good people in England to know it too, that they may break our chains, and set us free.”

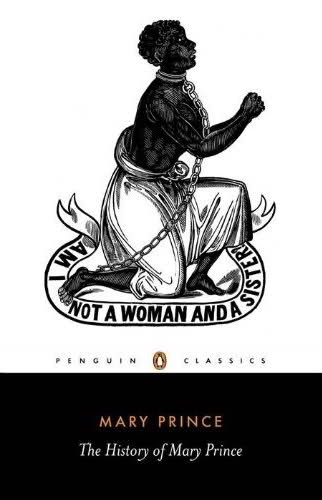

The publication in England in 1831 of ”The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave, Related by Herself” galvanised that country’s abolition movement.

The story of Mary Prince’s life as a slave in Bermuda and the West Indies was widely read by the general public and lawmakers alike at a time when the country was beginning to debate the abolition of slavery in the British colonies.

The book was so popular it went into three editions and Mary Prince became a household name in Britain.

Mary Prince’s ”History” was especially revealing as it was the first time a female slave’s life story was published in England — where slavery was illegal — complete with tales of murder, torture, sexual abuse and general mistreatment.

“They can’t do without slaves, [Bermuda and the British West Indian colonies] say,” said Mary Prince at the conclusion of her book. “What’s the reason they can’t do without slaves as well as in England? No slaves here –no whips — no stocks — no punishment, except for wicked people. They hire servants in England; and if they don’t like them, they send them away: they can’t lick them. Let them work ever so hard in England, they are far better off than slaves.

“If they get a bad master, they give warning and go hire to another. They have their liberty. That’s just what we want. We don’t mind hard work, if we had proper treatment, and proper wages like English servants, and proper time given in the week to keep us from breaking the Sabbath …

“This is slavery. I tell it, to let English people know the truth; and I hope they will never leave off to pray God, and call loud to the great King of England, till all the poor blacks be given free, and slavery done up for evermore.”

Her appeal to British sensibilities — and her graphic descriptions of slavery in Bermuda and the West Indies — are generally credited with helping to lead to the institution’s abolition in British territories in 1833.

In England, common law prohibiting the ownership of slaves was first established in 1772 and the transatlantic British slave trade had been banned in 1807.

After being bought and sold by a string of increasingly vicious owners, Mary Prince — born near Devonshire Marsh in 1788 — was brought to London in 1828 where she soon fled her owners with the help of a local church.

She went on to find shelter and work in the home of abolitionist writer Thomas Pringle. To a friend of the writer – who transcribed and edited the memoir – she relayed her story of pain, endurance and hope.

Recently British Labour MP Diane Abbott said that, as a black woman in those times, Mary Prince took a tremendous gamble in speaking out.

“She put herself at risk by telling her story and it’s very important that we remember the slaves who took part in the struggle to abolish the slave trade,” said Ms Abbott, who attended the recent ceremony to dedicate a plaque in London to Mary Prince’s memory.

Premier Paula Cox & Bermudian BBC News Announcer Moira Stewart At The Mary Prince Plaque Dedication

The location of the plaque — at University of London’s Senate House — is the site of the house where Mary Prince lived in 1829.

The Nubian Jak Community Trust, the UK group behind recent plaques dedicated to reggae singer Bob Marley and slave-turned-writer Ignatius Sancho, was responsible for the plaque.

The trust’s Jak Buela conducted extensive research into the story of Mary Prince and has said: “Mary Prince was an unsung hero of the movement to abolish slavery.” .

A white Bermudian descended from a Spanish Point sea captain who bought Mary Prince at auction played a key role in the plaque ceremony.

Mark Nash said he had read about the Mary Prince plaque — originally unveiled in 2007 and later removed while renovation work was being carried out at the Senate House.

“In 1805 Mary Prince was sold for fifty seven pounds to Captain John Ingham and his wife Mary of Spanish Point, Bermuda,” Mr. Nash said. ”Two hundred and six years — and six generations — later I found myself on the grounds of the Senate House at the University of London.

“As a direct descendant of Captain Ingham I had come, with my wife, to visit the historical plaque honouring Mary Prince, which was installed in 2007. It was very important to me to pay homage to this heroine who, along with other enslaved peoples, had been heinously brutalised by my family.”

Mr. Nash said he soon discovered the plaque was no longer in place because of the restoration work but before leaving the UK he contacted the Nubian Jak Community Trust.

“That is how I met Jak Beula and how I became involved in this ceremony,” he said.

American Poet Maya Angelou Introduces Readings From Mary Prince’s 1831 Memoir

Mr. Nash said he offered to pay for the cost of the new installation and to reimburse the Nubian Jak Community Trust for the original cost of the plaque.

“I didn’t offer to do this out of a sense of guilt but from a deep-seated belief that acknowledgement, apology and open dialogue are pathways to reconciliation and healing,” he said. “And reconciliation and healing are what we need, certainly in my country.

“In Bermuda, as in most of the Western world, we struggle with the aftermath of slavery and systems of oppression that still plague us today. Disparities in educational and employment opportunities, housing, healthcare, prison population, distribution of wealth, and overall life outcomes continue to exist along racial lines.”

Mr. Nash’s view thar Mary Prince’s narrative continues to resonate across the gulf of history — allowing modern-day readers to grasp “our common humanity” — is echoed by scholars.

One American academic recently said her legacy lingers on precisely because ”Mary Prince’s fight for justice went beyond her individual actions or freedom.”

“In the writing of her personal narrative, the enslaved Caribbean woman defines herself and undermines the power of the slave-owning class to control her by explicitly rejecting their definitions of her and who she is,” said Genise Vertus.

“Her efforts extend to a rejection of the slave-owning class’s definition of her fellow slaves also. Her voice rings true with the suffering of both black male and female slaves. The voice of the black woman also echoes with resounding clarity for future generations to come. ’I have been a slave—I have felt what a slave feels, and I know what a slave knows’. Hence, ‘hear from a slave what a slave had felt and suffered … till all the poor blacks be given free, and slavery done up for evermore’.”

Mr. Nash’s remarks appear in full below:

I would like to first acknowledge the Premier of Bermuda, the Honourable Paula Cox, JP MP. Thank you, Madame Premier, for representing our country today at this remembrance of Mary Prince, a true Bermudian heroine.

In 1805 Mary Prince was sold for fifty seven pounds to Captain John Ingham and his wife Mary of Spanish Point, Bermuda. Two hundred and six years (and six generations) later I found myself on the grounds of the Senate House at the University of London.

As a direct descendant of Captain Ingham I had come, with my wife, to visit the historical plaque honouring Mary Prince, which was installed in 2007. It was very important to me to pay homage to this heroine who, along with other enslaved peoples, had been heinously brutalised by my family.

After four hours of looking we finally determined that the plaque was no longer in place. Before flying out the next morning I contacted The Nubian Jak Community Trust as I knew they had been instrumental in having the plaque erected.

That is how I met Jak Beula and how I became involved in this ceremony. After learning that the plaque was shortly to be reinstalled after completion of building works, I advised Jak that I wished to pay for the cost of the installation. I’ve also committed to reimburse the original cost of the plaque in the form of a donation to The Nubian Jak Community Trust so that they can continue their good works.

I didn’t offer to do this out of a sense of guilt but from a deep-seated belief that acknowledgement, apology and open dialogue are pathways to reconciliation and healing.

And reconciliation and healing are what we need, certainly in my country. In Bermuda (as in most of the western world), we struggle with the aftermath of slavery and systems of oppression that still plague us today. Disparities in educational and employment opportunities, housing, healthcare, prison population, distribution of wealth, and overall life outcomes continue to exist along racial lines. While some would say progress has been made, it has come in fits and starts and has been offered begrudgingly by those that would take comfort in the status quo.

Whilst legislative remedies will be required to dismantle structural racism and provide racial equity and justice, it is authentic human interaction that will help bridge the spiritual divide.

I’ve heard it said that “coincidence is God’s desire to remain anonymous”. It was not coincidence that brought me into Jak Beula’s life just weeks before this plaque was to be unveiled. The universe has provided me an opportunity to provide, in some small way, a form of reparations on behalf of my family. The question is, what happens next?

As a white person, it’s important for me to recognise that the pain of slavery still exists today. Just as the trauma of slavery was passed intergenerationally to descendants of enslaved peoples, I often think about what was passed down through the generations of their oppressors. What human part of themselves did my ancestors have to close off to inflict such treatment on other human beings, to literally whip one woman to death as was recounted in Mary Prince’s autobiography? I believe that we sacrificed a part of our humanity, perhaps the ability to form true authentic relationships with “the other”. But I don’t believe that our spiritual condition is immutable. I believe that, walking through fear and discomfort, we can and should acknowledge the past and apologise for our ancestors’ part in it.

I believe we should openly discuss the disparities that continue to exist along racial lines, how they were borne in slavery and how they continue today, in large part, through apathy and implicit acceptance of inequality as the way of the world. I believe that through embracing our common humanity and forming truly authentic relationships across racial lines we can build a community that can achieve racial equity and racial justice.

Thank you Mary Prince, for your life, for your amazing strength and courage. Thank your for being a driving force for change and for a lifetime of fighting your oppressors. Thank you for sharing your story, which significantly contributed to the abolition of the slave trade. I extend my apologies on behalf of my family, for what we did to you and to others we enslaved. I pray that in my lifetime, following your incredible example, I can help bring us closer to a world where skin colour favours no one.

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Articles that link to this one: