Sally Bassett & ‘The Dangerous Spirit of Liberty’

Bermuda’s role in what was called the “contagion” of slave rebellions which spread throughout Britain’s Caribbean and North American colonies in the late 18th century was scrutinised at a recent University of the West Indies forum.

In the story Sarah (Sally) Bassett, one of the most renowned figures in Bermudian history and folklore, was singled out for particular attention by historian Justin Pope in his October 15 presentation at the university’s Cave Hill Campus in Barbados entitled ”A ‘Dangerous Spirit of Liberty’: The Spread of Slave Resistance in the British Atlantic, 1729-1845″.

“Perhaps Governor Trelawney of Jamaica summed up the British colonial perspective best when he penned a letter to the Duke of Newcastle in 1737: ‘The negroes in many of the British plantations … have of late been possessed of a dangerous spirit of liberty’,” said Mr. Pope. ” ..

There is evidence that slaves spread resistance between colonies during the 1730s. Historians are correct to be wary of the testimony of anxious British authorities, but we have too long ignored what white colonists saw and understood implicitly. They observed that their empire overlapped with a growing community of enslaved people that travelled between country and town, island and mainland, and in so doing, carried the seeds of widespread resistance against New World slavery.

“Beyond the testimony of nervous white planters, there is evidence that slaves transmitted rebellion between the colonies of the British Empire and the wider Atlantic World.”

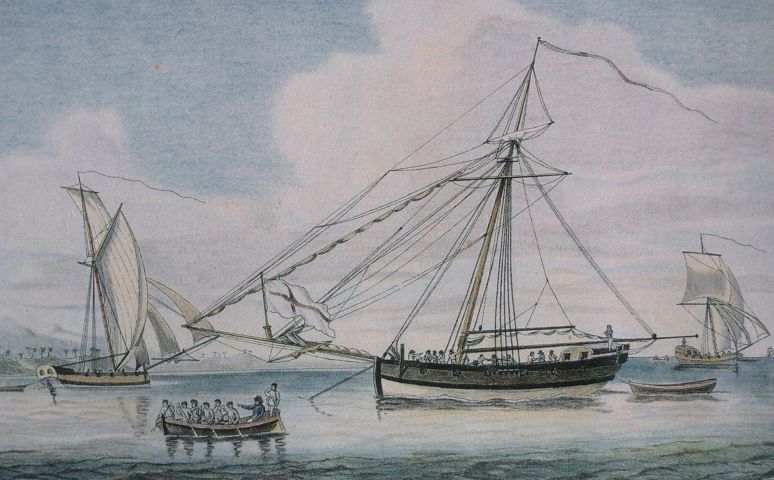

Mr. Pope said Bermuda’s mobile population of enslaved mariners, who built and manned the island’s fleet of fast-running Bermuda sloops, were uniquely well placed to observe and absorb new ideas and new realities — and to perhaps carry the seeds of rebellion throughout the New World.

“In 1733, the island’s Governor Pitt counted 200 white sailors and 150 slaves aboard local vessels, putting the percentage of Bermuda slave mariners above forty percent,” said Mr. Pope. “Because the ocean-going carrying trade was so extensive in Bermuda, it is likely that the vast majority of these black mariners crewed ships that travelled throughout the Atlantic Ocean.

“Significantly, Bermudian slaves were the consummate black sailors of the British Empire during the 1730s. Tobacco agriculture had declined on the island by the late 17th century, so that white colonists abandoned plantations for ships and pushed bowlines into the hands of their slaves. The Bermuda sloop emerged as a favorite carrying vessel because of the native cedar construction of its hull and shallow draft, which allowed for trade far up inland rivers. The fact that slaves worked aboard so many of these ocean-going vessels meant that they had access to a variety of plantations in the mainland and West Indian colonies. Perhaps no other British colonial slave society ranged so far.”

Bermuda’s seagoing slaves could be found aboard sloops which travelled the slave coast of Africa, carried trade throughout the West Indies and anchored in the crowded harbours of New York, Philadelphia and Boston.

“Not surprisingly, they could also carry weapons of resistance between slave societies, share news, and be swept up in conspiracy scares in British ports,” said Mr. Pope.

The historian said the discovery of a single African “white toade” in Bermuda during the investigation into the 1730 Sally Bassett poisoning conspiracy underscored the geographic mobility of the island’s slave sailors.

” In the winter of the previous year, the family of white mariner Thomas Foster became terribly ill, including his wife Sarah and the house slave Nancey. However, the other household slave girl, Beck, seemed unaffected by illness. At some point during the spring, white officials accused young Beck of poisoning the Foster family. She, in turn, confessed that the previous December, her grandmother, Sarah Bassett, had helped her poison the household.

In the trial transcript, Beck described the various poisons her grandmother carried into the Foster kitchen in December of 1729, one “white werewith to poyson her said master”. The white substance, Beck said, was a “white toade”. Supposedly, elderly Sarah Bassett gave specific instructions to Beck to place the white toad in the “victuels” of her master and mistress.

Mr. Pope said the use of white toad — a fetish in some African and Caribbean ceremonies — in the poisoning plot pointed to Sally Bassett having a collaborator in Bermuda’s sea-roving slave community.

“The ‘white toade’ described by the young woman’s testimony suggests that a traditional African weapon had been carried into the colony by a slave mariner,” he said. “There were no indigenous white toads in Bermuda. However, as noted by the Bermudian historian Clarence Maxwell, poisonous toads were used in ceremonies among Akan speaking peoples in the tropical forests of West Africa and carried into the voudou traditions of San Domingue.

” … According to anthropologist E. Wade Davis, the skin of the toad contains toxins that serve, in small doses, as muscle relaxants. A large dose is capable of causing respiratory failure. Administering the toad’s skin through food, as Sarah Bassett supposedly instructed her granddaughter to do, would probably have caused a severe reaction. If there really was a white toad used in the Bermuda poisoning conspiracy, then it was almost certainly brought to the colony by a slave mariner who believed he was arming a spiritual practitioner against her enemies. It was not something that Sarah Bassett could have asked for lightly. The person who purchased the item would have easily been able to discover, or at least suspect, its usage. Whoever carried it had to be trusted. The toad would have had to been captured or cultivated in the tropical forests of West Africa or northern South America, purchased in the slave markets of towns like Paramaraibo, on the Surinam River of Dutch Guyana, or in the markets of Elmina, on the southern coast of West Africa. We can only surmise the origins of the poisonous toad, yet it’s very presence on the island of Bermuda suggests a trade in poisons, betweens slave societies and through the hands of black mariners.”

When Sarah Bassett was burnt alive at Crow Road in 1730, the public spectacle of her death was meant to serve as a grisly warning to other slaves to abandon plots against their oppressors. However, Mr. Pope points out in the ensuing years other poisoning conspiracies were unearthed in Caribbean and North American colonies — suggesting Sarah Bassett’s story had been communicated through the black Atlantic world by Bermudian mariners, inspiring “other obeah women in the colonies (to) hand out poisonous amphibians.”

However, the historian concluded by saying the most crucial role played by seagoing Bermudian slaves in the 18th century centred not around any contraband trade in weapons or poisons but rather the trade in ideas about cultural identity and liberty they engaged in.

” … Maritime slaves formed a very real black Atlantic during this period of intensified slave resistance,” he said. “They traveled throughout the British Empire, crewing ships and participating in the burgeoning oceanic trade. They circulated traditional African weapons, like the white toad of Bermuda …

” But the most significant contribution of this enslaved maritime community lay not simply in the threat of physical revolt, but in galvanising diverse slave societies throughout the British Atlantic to rise together against their oppressors.”

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Articles that link to this one: