The Dual Legacies Of Denmark Vesey

Ground was broken last year for a South Carolina monument commemorating the former slave of a Bermuda sea captain accused of organising the largest slave revolt in American history — but uncertainty continues to cloud the true legacy of Denmark Vesey.

Ground was broken last year for a South Carolina monument commemorating the former slave of a Bermuda sea captain accused of organising the largest slave revolt in American history — but uncertainty continues to cloud the true legacy of Denmark Vesey.

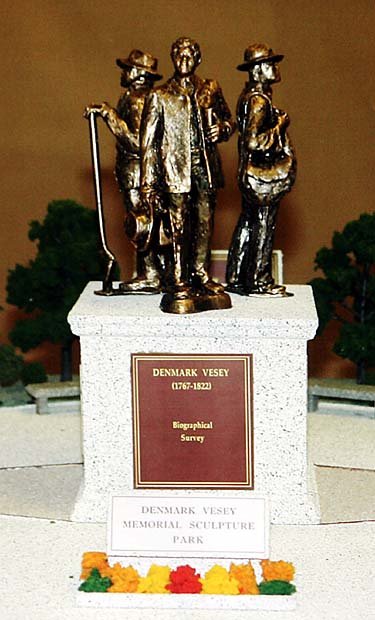

The memorial, designed by celebrated American sculptor Ed Dwight, will stand in Charleston’s Hampton Park.

Denmark Vesey was hanged in 1822 after being convicted of plotting an uprising supposedly intended to burn Charleston to the ground [an artist's impression of the accused insurrectionist used on the cover of a 2000 biography appears here].

But historians remain divided as to whether he indeed attempted to mobilise armed resistance against slavery in South Carolina or demonstrated another kind of heroism altogether — going to the gallows rather than testify against fellow blacks during a trial perhaps based on scare-mongering by an office-seeking Charleston politician.

Few historians today, given the climate of racial fear which swept Charleston, South Carolina during the summer of 1822, would argue with any degree of certainty there actually was a “conspiracy” designed to emulate the wholesale insurrection which took place in Haiti a generation earlier, resulting in the deaths of 100,000 blacks and 24,000 of the 40,000 white colonists.

In fact, some scholar argue the real “conspiracy” was not Denmark Vesey’s supposedly suppressed slave revolt but rather a secret plan by an ambitious white politician to kill blacks, resulting in the largest number of executions ever carried out by a civilian court in the United States.

Denmark Vesey is thought to have been born in 1767, in either Africa or on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas.

As a boy of 14 he was taken to Cap Francais, in St. Domingue — as Haiti was then known — by the captain of a Bermuda slave ship, Joseph Vesey.

Named Telemaque at the time [after Telemachus, son of the Trojan War hero Odysseus], he was sold there as part of a cargo of 390 blacks destined for the island’s sugar plantations. Declared “unsound and subject to epileptic fits,” the boy was returned for credit on the slaver’s next visit to Cap Francais.

For 18 years he was kept by Captain Vesey as a personal servant and is thought to have spent considerable time in Bermuda during this period, learning to read and write.

Short Documentary On Denmark Vesey’s Alleged Plot

In 1783, tiring of the sea, Joseph Vesey settled not in his native Bermuda but rather in Charleston and established a prosperous business as a slave broker and ship chandler.

Denmark Vesey was taught the carpentry trade, permitted to earn sums of money for his own use.

He bought lottery tickets in 1800 and won $1,500 in a draw, purchasing his freedom for a $600 share of the lottery prize.

For 22 years, Denmark Vesey practiced his trade as a free man in Charleston, acquiring property valued at $8,000.

Though he was free, his several wives and children remained slaves. He joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church where the seeds of his supposed rebellion were allegedly sown.

In 1820 or 1821, according to evidence presented at his trial, he began to plot the insurrection. He is said to have recruited a secret army of as many as 9,000 slaves who, on his signal, were to march on the city and destroy it.

Slave blacksmiths were ordered to forge pikes and bayonets. Stable boys, draymen and carters were responsible for making horses available, and boatmen were assigned to ferry slave companies from nearby plantations.

The US Arsenal on Charleston Neck was to be seized, and the Guardhouse attacked. The Governor was to be summarily executed.

When a sufficient supply of arms was in the hands of the insurgents, the city was to be put to the torch and white Charlestonians, to the last man, woman and child, were to be slaughtered.

The revolt’s final phases included the seizing of ships in the harbour and an exodus of freed slaves from burning Charleston to Haiti, which had become the first black-ruled country in the Western hemisphere in 1804.

While these charges were laid against Vesey and others accused of conspiring with him, nobody knows the truth. Johns Hopkins University history professor Michael Johnson has argued that Charleston’s politically ambitious mayor James Hamilton Jr. dreamed up the alleged plot — compelling slaves he and his supporters coached to testify to the supposed details — to discredit his rival, Governor Thomas Bennett Jr. and advance his own career.

Indeed, Hamilton became a member of the US Congress in December, 1822, capitalising on the notoriety he gained bringing Denmark Vesey and his alleged co-conspirators to trial just months earlier.

Prof. Johnson has said this interpretation of Denmark Vesey’s story illustrates a different kind of heroism: the heroism of Vesey and the other 44 men who pleaded not guilty and refused to testify falsely against fellow slaves–men who made the terrible choice to face execution for telling the truth rather than send others to the gallows on the basis of a lie.

Indeed, the overwhelming majority of the men arrested refused to testify falsely, despite extensive torture.

The Story Of Denmark Vesey’s Charleston Church

Prof. Johnson concluded: “It is time to pay attention to the not guilty pleas of almost all the men who went to the gallows,” to honor them for “their refusal to name names in order to save themselves.”

The arrest, trial and execution of Vesey and other alleged conspirators took place in an atmosphere of near hysteria, despite, or perhaps because of, a virtual news blackout imposed for a fortnight by city authorities.

Blacks then clearly outnumbered whites in the city. The census of 1820 had counted 11,654 whites, 12,652 slaves, and 1,475 free blacks. When South Carolina’s plantation blacks were factored in, the black majority was overwhelming.

In all, 131 blacks and four whites were arrested and put on trial. As Prof. Johnson has pointed out, 27 white Charlestonians testified in court in support of 15 black defendants, resisting the hysteria sweeping the city. Bermudian Captain Joseph Vesey would himself testify that Denmark Vesey had always been loyal and intelligent and did not provide any incriminating evidence against his former slave.

Ultimately, though, 35 blacks were hanged. None of their bodies — including Denmark Vesey’s — appear to have been released to their families for Christian burial.

Denmark Vesey’s Charleston Footprints

The Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 110 Calhoun Street. In 1791, the Free African Society, composed of slaves and free blacks, was organised in Charleston. In 1818 several congregations became of part of the Richard Allen movement – the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1818 a modest house of worship was erected at Reid and Hanover where Denmark Vesey was a Class Leader.

In 1818, 1820 and 1821 the City closed the church prosecuting its leaders for meeting without white supervision. In 1822, after the hangings of Vesey and other church members, the church building was razed. The structure was rebuilt and worship services continued until 1834 when the few independent black churches were outlawed. After 1834 many of these churches continued to worship underground. In 1865 as the Civil War drew to a close, the congregation was named the Emanuel AME Church and a house of worship at 110 Calhoun St. was built. Every craftsman who worked on it was of African descent. The architect, was Robert Vesey, the son of Denmark Vesey. The church structure, damaged in an 1886 earthquake, was rebuilt in 1892 and is the oldest AME church in the South.

Denmark Vesey House, 56 Bull Street. At the time of Vesey’s execution his home was listed at 20 Bull St. In 1976, 56 Bull Street was listed as a US National Historic Landmark and is commonly referred to as the Denmark Vesey House.

Portrait of Denmark Vesey in Gaillard Auditorium, 77 Calhoun Street. As no physical description of Vesey is known to exist, any picture of him is an artist’s conception. This portrait by Dorothy B. Wright shows him from the back addressing his followers. The portrait, hung in 1976 — more than 150 years after Vesey’s public hanging — prompted criticism, and the theft of the painting. After Charleston Mayor Joe Riley said the city would commission a replacement if the painting remained missing, it was returned and more securely mounted.

Hanging Tree and Grave. Denmark Vesey and five others were allegedly hanged on North Line Street between King and Meeting. It is also claimed they were hanged from the Ashley Avenue Oak Tree. The locations of the graves of the 35 hanged in the aftermath of the Vesey Conspiracy remain unknown.

“Denmark Vesey: Spirit of Freedom Monument” Hampton Park, 30 Mary Murray Drive. A statue of Vesey originally planned in 1996 for the historic district was held up until a compromise was made to erect the statue in Hampton Park — away from the general tourist district. Sculptor Ed Dwight has created a prototype of a bronze statue of Vesey and the other ringleaders, Peter Poyas and Gullah Jack, standing atop a five-foot granite pedestal on a plaza. Ground was broken for the memorial in 2010 but fund raising efforts continue.