Helium Played Dual Role In Sealab Experiment

While it is probably best known for giving people squeaky voices when we inhale it, helium has also been used extensively within so-called “breathing gas,” an atmospheric mixture used for human respiration when it otherwise wouldn’t be possible.

In 1964, during a series of tests run by the United States Navy, Bermuda’s waters played host to the early development of helium-rich breathing gas.

It was during that year that Sealab I, an underwater habitat developed by the U.S. Navy, was lowered a few miles off of the island’s coast, intended to study the effects of extended periods of working and living underwater.

On July 22, 1964, four Navy divers submerged to a depth of 192 feet, and surfaced over a week later on July 31 in what was a ground-breaking experiment during that era. All four divers were in relatively good health upon surfacing, thanks in large part to the role of helium in allowing them to breathe freely within Sealab I.

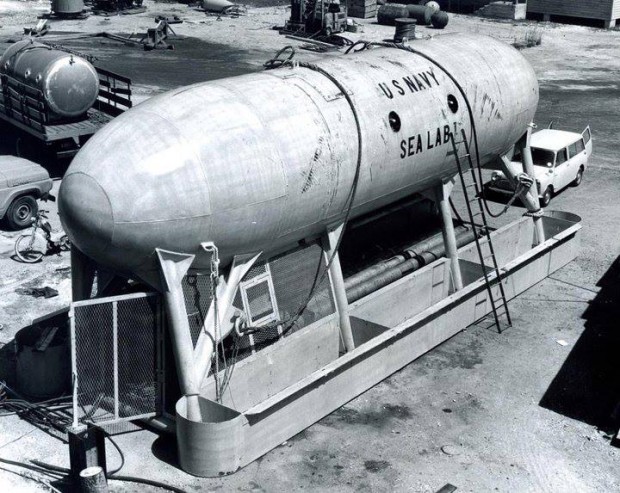

Sealab I on land at the U.S. Naval Station in Bermuda in 1964:

Because Sealab I required an atmosphere of some kind in order for the divers to breathe while within the underwater habitat, the United States Naval Institute developed “breathing gas,” a mixture of helium, oxygen, and nitrogen that allows for human respiration.

The U.S. Naval Institute reported that, following a series of tests in which animals were exposed to selected mixtures of the compounds, it was found that the test subjects survived a 14-day exposure at a simulated depth of 200 feet and could also be returned safely to surface pressures with no physiological damage.

When the animal-based experiments were completed in 1962, the Secretary of the Navy authorized the use of human beings in the tests. A group of volunteers was first exposed to an essentially nitrogen-free atmosphere for a period of 144 hours.

Despite being relatively rare in the air – it comprises only 0.00052 percent of Earth’s atmosphere by volume – the U.S. Navy’s breathing gas consisted of 74.4 percent helium.

Conversely, Earth’s atmosphere contains a very high level of nitrogen at 78.09 percent, while that compound accounted for only 4 percent of the breathing gas. Only oxygen, at 20.95 percent in the atmosphere and 21.6 percent in the breathing gas, was comparable by volume.

The human trials, using two of the men who later participated in the Sealab project, were run at a simulated 200-foot pressure depth and proved to be successful.

Following the array of tests, Sealab I became the first exploratory attempt to achieve laboratory results under actual conditions off the coast of Bermuda.

It was following the resurfacing of the divers from Sealab I that the US Naval Institute said that helium, while serving an unlikely purpose as an agent in breathing gas, had some unintended effects on the divers.

Their findings reported that the “human voice acquired a difficult-to-understand Donald Duck sound. This is due to the higher speed of sound in helium and the effect it has on the resonating quality of the body’s respiratory air spaces which control vocal sounds.”

The Navy said that, since the divers’ voices became almost intelligible, the “need to develop a means of making diver-to-diver and diver-to-surface communication understandable was obvious.”

“It was found that a special filtering device – the U.S. Navy Applied Science Laboratory helium speech modifier – greatly improved the intelligibility of communications from the Sealab habitat to the surface control center.

“Thus, the helium speech problem has been solved for the undersea habitat.”

Aquanauts enjoying a meal in SeaLab 1 submerged off Bermuda in 1964:

Sealab II repeated the use of helium in breathing gas, and aquanaut Scott Carpenter spent a total of 30 days below the surface of the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California in the experimental underwater habitat.

That endeavor set a world record, and was also notable in that Carpenter had already traveled to space, and so became the world’s first person to have been both an astronaut and aquanaut.

Carpenter was also supposed to take part in the first Sealab mission in Bermuda in 1964, and traveled to the island in preparation.

However, a few days before the experiment was to get underway, the former astronaut crashed his rental scooter while on the island, breaking his arm in the process. He was traveling back to the Base from Hamilton when he had his accident.

He was treated at the hospital on the former Naval Base in Bermuda, before flying back to the United States to recuperate. He was replaced by another diver, then became a part of the Sealab II mission the following year.

After Carpenter’s historic 30 days underwater, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson wanted to speak to the aquanaut to extend his congratulations.

Helium came into play in its quirky way.

When President Johnson’s invitation was extended to Carpenter, the diver was still in a decompression chamber in order to recuperate from his mission; the chamber maintained a helium-rich atmosphere.

Despite his high-pitched voice, Carpenter took President Johnson’s call, with the phone operators suspecting that there was a problem with the connection when they heard the diver over the phone. Still, the call went ahead, and Carpenter was able to receive the President’s congratulations.

Aquanaut Scott Carpenter speaks to U.S. President Lyndon Johnson with his squeaky helium voice:

Probably best known for making balloons fly into the sky, helium is a relatively rare compound which is also essential in research and medicine. According to a 2012 Guardian report, some scientists feel is being too quickly squandered.

Oleg Kirichek, the leader of a research team in the United Kingdom, once had to cancel one of his key experiments because the facility had run out of helium.

Kirichek said, “Yet we put the stuff into party balloons and let them float off into the upper atmosphere, or we use it to make our voices go squeaky for a laugh. It is very, very stupid. It makes me really angry.”

Professor Robert Richardson, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1996 for his research on helium, argues that a helium party balloon should cost over $100, to reflect the true value of the gas used.

“We are squandering an irreplaceable resource,” he said.

Read More About

Category: All, History, technology