Column: Horner On Climate Crisis, Fibre Trends

[Opinion column written by Patrice Horner]

‘Commodities amid the climate emergency’ was the focus of the Global Commodities Forum in Geneva in December, hosted by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTAD]. The intensifying climate crisis is upending global commodity value chains, disrupting production, destabilizing supplies, and driving price volatility. In this session on Promoting Natural Fibers, its the clothes on our back that are contributing to plastic pollution and green house gases.

Elke Hortmeyer is the chairperson of the Discover Natural Fibers Initiate [DNFI]. She is from the cotton industry. Synthetically produced fibers are called manmade fibers. The production of natural fibers that binds people and community. Countless people earn their living in agriculture by growing fibers or managing animal farms. The demand for textile fibers is immense. Natural fibers are not always the most cost-effective solution but perhaps in the future we will no longer be faced with a question of what is cost-effective but what is biodegradable or what supports the natural cycle or integrated into a recycling process.

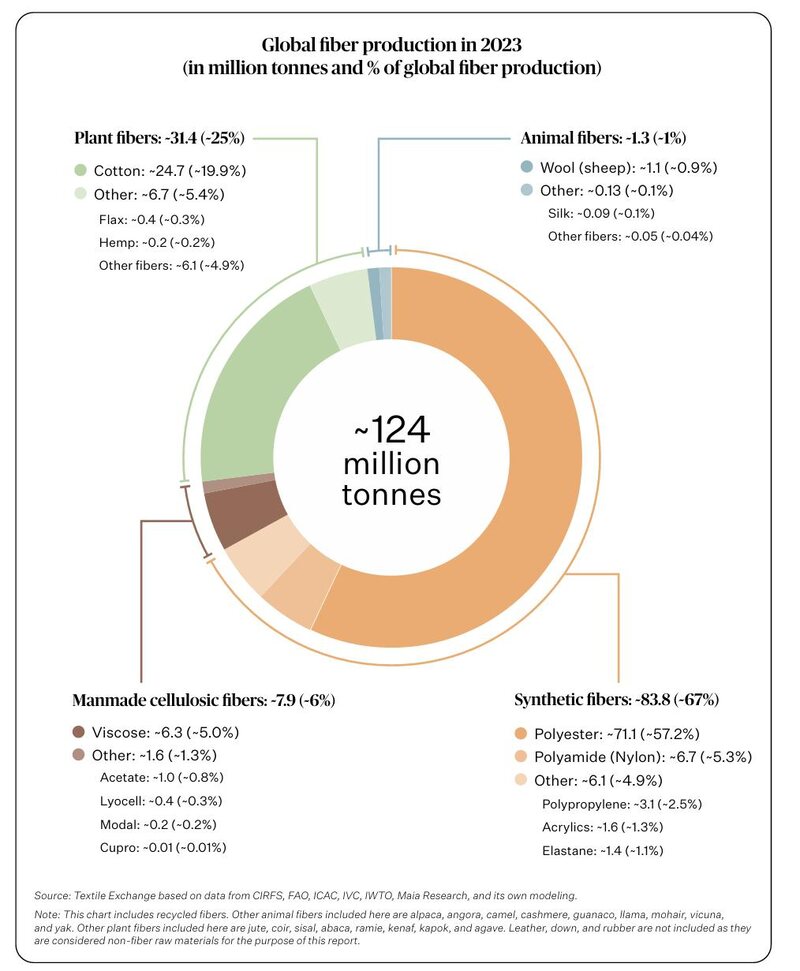

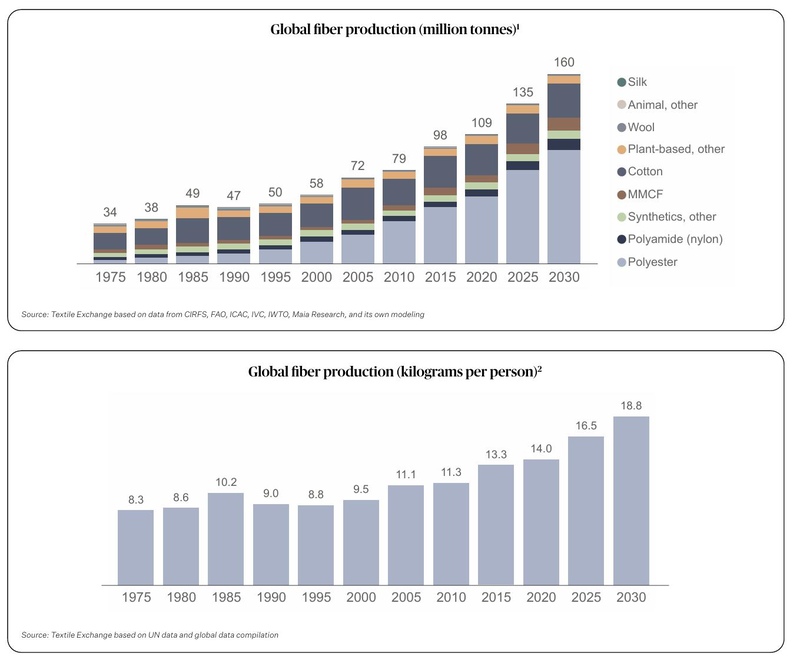

There are four groups of fibers are in production: plant, animal, manmade, and synthetic. Global fiber production represented 124 million metric tons in 2023 while it was about 50 million tons 30 years ago. This provides an idea of the explosive growth in fiber production. It has stabilized since 2020. Manmade fibers have dominated since 2005-2010, reported Marco Fugazza an economist at UNCTAD with expertise in trade policy, agricultural commodities, maritime connectivity and trade agreements.

Manmade fibers contributed to over 70% of total fiber production. Cotton contributed about 20%. Other vegetable fibers about 6% and animal fibers about 2%. There is a shift in consumer preferences towards something more sustainable or a blended fabric. The trade in raw vegetable fibers excluding cotton has grown, such as flax for linen. With stable figures over the past five years, vegetable fibres dominate in select industries despite competition from manmade alternatives.

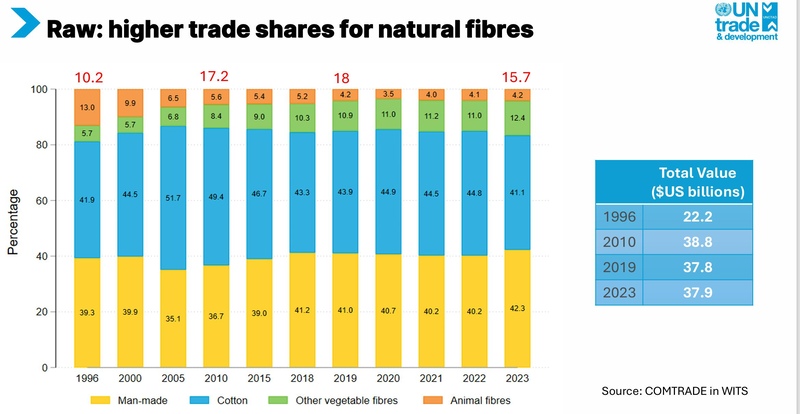

For trade, there are three types of fiber products: raw, yarn, and fabrics. The total trade values for raw materials has experienced significant growth since 1996, peaking at almost $40 billion in 2010 before stabilizing at approximately $38 billion in 2023. Manmade fibers are not as dominate in trade as in production. The total trade share of natural materials volumes has increased over the past 30 years but has leveled off at around 40% in the last decade.

Trade in cotton, gene cotton, and other vegetable fibers make up roughly a quarter of total production of these fibers. The highest trade share with animal fibers accounted for almost 40% of production, whereas only $4 in raw trade. Trade in manmade fibers to be processed accounts for only around 8% of total production. This indicates that the manmade fibers are processed predominantly within producing countries, whereas natural fibers are processed across multiple countries and regions.

So as far as yarn is concerned, by 2023 the total trade value reached approximately $40.5 billion up to $26 billion in 1996. Incredibly, yarn has traditionally been dominated by manmade products maintaining a share of about two-thirds of total volumes. Manmade yarns meets most industrial needs leaving limited growth for natural fiber yarns. The trade in fabrics also shows a dominance of manmade materials with their shares steadily increasing from 2005 to 2019 and stabilizing around 17% in the past five years. In 2023, trade value had moderated to approximately 40.8 billion. It peaked at over 45 billion in 2015.

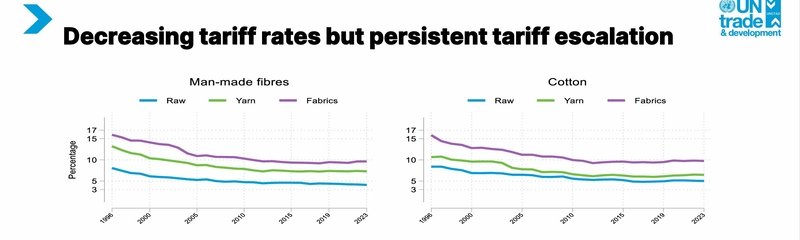

Tariffs in the fibers industry have decreased from 1996 to 2023 with some convergence across the fiber groups. Higher tariffs apply to cotton and manmade fibers compared to other vegetable and animal fibers for both raw products and yarn. Whereas for fabrics versus for raw materials, similar rates apply to manmade, cotton and animal fibers. The level of tariff escalates with the level of processing as shown in the graphs. The higher tariffs hinder the ability to add value for countries generating raw fibers and limit their ability to advance in the value chain.

Nontariff measures [non-trade measures] differ widely across countries and fiber types. Natural and animal fibers particularly in their raw form are subject to more regulations than manmade fibers. As agricultural products they face higher levels of sanitary and phytosanitary measures along with technical barriers to trade, driven by environmental and health concerns. The combination of tariff escalation and NTMs potentially reinforces existing industrial advantages and challenges developing countries’ efforts again to move up the value chain. Segments of fibers value chains show high concentration with the top three players often controlling 60%.

There are three major models for complete integration for raw material to textiles. Countries such as China and India follow a fully integrated approach managing all stages of the value chain to maximize economies of scale. China’s model is primarily export driven while India’s approach balances both domestic and international markets.

The processing focused integration include nations like Turkey and Vietnam which focus on processing relying heavily on imported raw materials for export-oriented production. The third model is specialty integration. Italy targets high value segments emphasizing quality over quantity, often due to higher labor cost and limited raw materials production.

Twenty 20 years ago the system of import quotas governed by the Multi Fibre Arrangement [MFA] followed by the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing [ATC], which was removed in 2005, unleasing the current landscape of the fiber and textile sectors. The expected role of man-made fibers in the post-quotas era was not fully anticipated. Natural fibers are finding new opportunities due to increasing awareness of environmental and social sustainability within the textile industry.

However, traceability requirements could elevate costs and dampen demand. Efforts to reduce greenhouse gases emissions from synthetic fibers may diminish their competitiveness. Border carbon adjustment policies could potentially extend to include products with high greenhouse gases footprint such as manmade synthetic fibers and textiles.

Robert Antoshak with over 30 years of experience in the fiber and textile industries, is a partner at the GURCI textile organization managing the USA office, with extensive expertise on marketing, mergers and acquisitions, sourcing, strategic planning and trade negotiations. He has advised the U.S. government on trade agreements including for North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA] and the World Trade Organization [WTO].

Global fiber consumption for cotton has been flat in recent years, but cotton had lost net growth in global fiber consumption over the decades. U.S. imports of apparel has moved towards synthetics. In 2011-2012, the price of cotton soared globally to over $2 a pound. Brands moved to synthetics as a replacement for cotton which was accepted by customers There has been a trend toward imports of synthetics from all over the world into the U.S. market. Government policy promoted the move away from perspective of cotton as well.

Around 2018 when the Section 301 on tariffs on Chinese products went in place, there was a rush in the industry to find cheaper inputs. China’s overcapacity of polyester is priced far below cotton. Price increases posed by Section 301 were absorbed into the consumer prices. The irony was the cotton farmers were hurt in 2001 during the first Trump administration, who at the time was a key constituency who ended up getting harmed by the action. Manmade fiber prices continue to come down. After 2018 cotton has followed its way down, but man-made fiber increased the market share with end uses.

The global fashion industry makes about 100 billion garments a year. Fast fashion prefers synthetics. Slow fashion would be traditional small brand manufacturing. Fast fashion are some of the biggest brands in the world right now, that create huge quantities of product. Gap does 12,000 styles a year. H&M cranks out 25,000 new styles a year. Zara does 36,000 new styles a year. But Shein has 1.3 million news styles per year. Huge quantities of synthetic fibers that are being used in their product.

The Shein model or the Temu model or the Amazon model drive constant churn of new styles for consumers and favors synthetics because it’s easily replaceable, easy to manufacture, and the prices are low. Fast fashion is forecast to grow by about 12% of the U.S. apparel sales by 2027. Polyester is gaining all the net share of manmade fiber consumption globally. A lot of this product ends up in land fills and it doesn’t biodegrade. It adds to the environmental calamities that the planet is now facing.

There are innovations coming out of the cotton industry that are going to really astound farmers and provide opportunities. Technology is going to play a role to help solve this fiber war problem. Slow fashion tends to favour cotton and other value-added fibers like that. A lot of the creativity in the garment business comes from slow fashion. It doesn’t come from fast fashion. The government may need to step in with a more comprehensive approach to implement sustainability standards or some ways of encouraging more intelligent consumption other than overproducing in the fashion industry.

Cotton Carbon Foot Print

The pricing for cotton doesn’t capture all the positive externalities it brings into our global community. Eric Trachtenberg is the Executive Director of the International Cotton Advisory Committee [ICAC]. It represents the entire cotton value chain from seed to the end consumer.

It is biodegradable, which means less waste. It has a potential to reduce poverty and conflict, especially in Africa. It grows in dry conditions where other crops can’t. It is a tool for women’s empowerment as 43% of cotton farmers are women. It can be a positive force against climate change. Cotton can sequester carbon including in its stalks and roots. The success for cotton sector will depend on our ability to make the case to governments, consumers, civil society, and the private sector that cotton is a global public good.

Cotton can sequester half a kilogram of additional carbon dioxide per kilogram. The fibers are mostly cellulose. Products like carbon fabrics and furniture made from cotton stocks also can hold carbon for several years until disposal. Cotton stalks are processed into biochar and incorporated into the soil, where it can sequester carbon for 100 years. Biochar in an important innovation for cotton.

It can have a very large impact in terms of carbon reduction in the atmosphere. As a source of revenue for ecosystem services of product environmental footprint [PEF] such as carbon credits. It could be profitable for small farmers. This makes a serious case for brands and consumers to use more cotton.

Linen, despite its higher price versus other natural fibers, is affordable luxury and is present in all of the market segments. Linen is a member of the PEF. European flax production has exceeded 1,200 companies that are certified. There is major credibility across all stages of the value chain.

- Patrice Horner

Read More About

Category: All, Environment