Backing For Bermudian’s War Grave Call

On this Remembrance Day weekend, Bermuda National Museum director Dr. Edward Harris urged locals to spare a thought for William Edmund Smith — the first Bermudian casualty of World War One [1914-1918].

On this Remembrance Day weekend, Bermuda National Museum director Dr. Edward Harris urged locals to spare a thought for William Edmund Smith — the first Bermudian casualty of World War One [1914-1918].

The Somerset man — who had worked at the Royal Naval Dockyard in Sandys Parish — left Bermuda to go to sea in 1912.

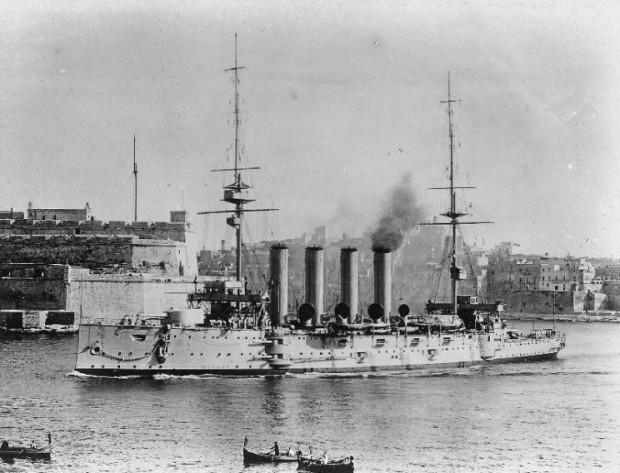

He was serving aboard the British cruiser HMS “Akoubir” [pictured] when it was torpedoed in the North Sea on September 21, 1914, just weeks after the war’s outbreak.

Mr. Smith and more than 400 of his “Akoubir” shipmates drowned in the German U-Boat attack that sank three aging British warships in just under two hours. A total of more than 1,400 Royal Navy servicemen were killed in the incident which established the submarine as a major weapon in the conduct of naval warfare.

Dr. Harris’ reasons for asking Bermudians to remember Mr. Smith in their prayers on this Remembrance Day were twofold.

First, he wants locals to honour the first Bermudian who died in a war during which 35 million people were killed or wounded by the time hostilities ceased on November 11, 1918 — the deadliest conflict in human history. At least 80 Bermudians who volunteered for overseas service in World War One were killed in action.

Secondly, the National Museum director is attempting to spotlight what he calls “the second destruction of HMS “Aboukir” by a Dutch salvage operation stripping the wreck of brass, copper and other scrap metals.

Dr. Harris has said war graves on land are considered to be sacred territory and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and respective governments place great emphasis on the maintenance and preservation of such sites in honour of those who gave their lives for our future freedoms.

But underwater sites are less well monitored, he said, as demonstrated by the ripping apart of HMS “Aboukir”, the final resting place of Bermudian Mr. Smith and his shipmates.

Calling the salvage operation “the desecration of a war grave”, Dr. Harris has condemned the “salvage” and renewed calls for the British Government to ratify the UNESCO Convention on Underwater Cultural Heritage.

Dr. Harris’ calls were echoed this week by the on-line British archeological/environmental group Mortimer — which takes its name from pioneering archeologist John Robert Mortimer.

Mortimer issued a statement condemning the “Akoubir” salvage operation, calling on the Dutch and UK governments to use the 1949 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of the Victims of War, which requires all signatory powers to respect the graves of the war dead along with the UK’s own Protection of Military Remains Act to call an immediate halt to the destruction of maritime war graves.

HMS “Akoubir” under steam

A spokesperson for Mortimer said: “This is an appalling precedent. If two European Union governments cannot protect the last resting place of these sailors using their own legislation and International Law, then no victims of war can rest in peace. This is a cross-party humanitarian issue and an issue of will.

“UK Prime Minister David Cameron must act immediately to reassure the descendants of these men and our modern armed forces, that we never forget their sacrifice and that their resting places will be protected from vandalism and greed for as long as it takes.”

The British Government might have “shamefully sold these wrecks for commercial gain in the 1950s”, added Mortimer, but it did not “sell the bodies of 1459 heroes and it cannot wash its hands of them now.”

Larry Burchall has written about Edmund Smith who, in in 1912, as a 20-year-old black Bermudian, joined the Royal Navy, left Bermuda, and sailed into Bermuda’s history.

The son of Mr. and Mrs. William F and Emma J. Smith of Sandys Parish, he initially joined the Royal Navy warship HMS “Sirius” as a cooks-mate said Mr. Burchall.

“HMS ‘Sirius’ was then a part of the Royal Navy’s North America and West Indies Squadron,” recounted Mr. Burchall. “This Squadron consisted of a large number of warships.

“The Squadron’s duty was to patrol the Caribbean and western Atlantic looking after the many bits of the British Empire scattered around and in the Atlantic triangle that stretched from what was then British Guiana [now Guyana], to British Honduras [now Belize] to Newfoundland [at the time not a part of Canada].

“The Squadron was based in Bermuda, and was commanded by an Admiral who lived in lordly splendour in Admiralty House, just above Clarence Cove in Pembroke.”

Mr. Burchall recounted how when HMS “Sirius” finished her two year West Indies Squadron commission, she returned to the UK and was paid off. That meant that her entire crew were sent on home leave and men due for discharge were discharged. Men continuing their naval service would come back at leave’s end and join a different Royal Navy ship.

“However, this young Bermudian had not actually joined the Roya Navy as a naval enlisted man,” continued Mr. Burchall. “Instead, he had joined as an auxiliary.

“So when HMS ‘Sirius’ paid off, he actually lost his job. Even though he was thousands of miles away from his Somerset home, and even though there was no possibility of a quick trip back home by a British Airways flight [ocean crossing passenger planes were still twenty years in the future], he was not fazed.”

So Mr. Smith signed on again in HMS ”Aboukir” — this time as an Officer’s Cook, 1st Class. This was a step-up from cooks-mate.

In 1914, HMS “Aboukir” was a 14-year-old four-funnel coal-fired ship-of-the-line designated as a cruiser. Since the Royal Navy was at that point shifting from coal- to oil-fired vessels, HMS “Aboukir” was already obsolete.

However, on August 3, 1914, when Great Britain went to war with Germany, every ship in the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet was pressed into service.

Dutch Divers inspect the wreck of HMS “Akoubir” in 2009

“That’s how this now 22-year-old Bermudian found himself at sea in the North Sea, at about 6:25am on 22nd September 1914,” said Mr. Burchall. “HMS ‘Aboukir’, along with HMS ‘Cressy’ and HMS ‘Hogue’, all three part of the 7th Cruiser Squadron of the 3rd Fleet, had been assigned a patrolling task that kept them at sea.

All three, “Aboukir”, “Cressy” and Hogue were torpedoed by a lone German submarine , the U-9.

“Aboukir” was hit first, and Commander Austin Tyrer on board HMS ‘Hogue’ later told what ensued:

“Someone told me that the ‘Aboukir’ had hit, or had been hit, by something…..the lame vessel slowly lost way… and began to heel over to port and settle by the head. The ‘Aboukir’ heeled over even more. Her crew were frantically trying to launch their boats.

“Finally abandoning the attempt, they tore off their clothes … and crawled on to the ships sides. Scores of other naked men had begun to claw their way down it. The rising sum glistened on their bodies and on the wet smooth steel plates of the vessel’s rounded bilge. Down they came slowly, inch by inch, some sitting, others standing, several lying flat.

“And then, suddenly, it was all over. The vessel had completely turned turtle and on all sides of her…the sea was literally black with a mass of struggling humanity.”

One man in that “mass of struggling humanity” might have been Mr. Smith, commented Mr. Burchall. When the survivors of HMS “Aboukir” were finally brought ashore, that young Bermudian was not amongst them. Fewer than 280 of the 700 man crew were saved.

“The men from HMS ‘Aboukir’ had come from all over England. One had come from Bermuda,” said Mr. Burchall. “To commemorate them, their names are inscribed on the Chatham Naval Memorial [pictured above], set on a hill overlooking the town of Chatham, Kent.

“This young Bermudian’s name is there. It’s listed with the names of his English shipmates. So there, on this monument in a corner of England, is a little piece of Bermuda that most Bermudians don’t know about. Sometimes, though, you’ll find his name published in a Roll of Honour in Bermuda.”