Video: Rudyard Kipling’s Bermuda Stories

Best remembered today for tales set against the vastness of British India in such works as “The Jungle Book”, “Kim” and “The Man Who Would Be King”, author and poet Rudyard Kipling used colonial Bermuda’s intimate scale to striking effect in two stories written towards the end of his life.

Best remembered today for tales set against the vastness of British India in such works as “The Jungle Book”, “Kim” and “The Man Who Would Be King”, author and poet Rudyard Kipling used colonial Bermuda’s intimate scale to striking effect in two stories written towards the end of his life.

Kipling [1865–1936], the first English-language writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, spent three months on the island in 1930 and later produced two short stories inspired by his time here — “A Naval Mutiny” [1931] along with an accompanying poem titled “The Coiner” [1932] and “A Sea Dog” [1934].

But unlike his fellow literary giant and friend Mark Twain, Kipling had been a reluctant visitor to Bermuda.

“That visit was a forced one; and he stayed far longer than he would have wished,” Bermudian Eileen Stamers-Smith told the London Kipling Society during a 1995 presentation. “By the 1930s the tourist trade, by the steamships regularly plying between the USA and Bermuda, had taken off. It was now fashionable to have a tan; so visitors were coming throughout the summer months rather than in winter.

“Prohibition was in force in the States, so the liquor stores on Front Street, Hamilton –originally set up to provide for sailors from the merchant ships — did booming business, making fortunes for a few ‘old’ and ‘new’ Bermudians. Kipling, a temperate man himself and by now no lover of Americans and their ways, was disgusted by the drunkenness he saw daily.

“Bermudians themselves, working hard in a sub-tropical climate, were often inclined to drink heavily; but it was the Yankees from the tripper boats who went straight across the road from the wharf to quench a bottomless thirst, and often had to be carried back to their ship dead drunk. That is why, in the opening passage of ‘A Naval Mutiny’, Kipling calls Bermuda not only ‘that gem of sub-tropical seas’, but ‘Stephano’s Isle’ – after the drunken butler in [Shakespeare's Bermuda-inspired play] ‘The Tempest’.”

A controversial figure in his own time and even now, Kipling was once labelled “the prophet of British imperialism” by George Orwell. More recently critic Douglas Kerr said: “He [Kipling] is still an author who can inspire passionate disagreement and his place in literary and cultural history is far from settled. But as the age of the European empires recedes, he is recognised as an incomparable, if controversial, interpreter of how empire was experienced. That, and an increasing recognition of his extraordinary narrative gifts, make him a force to be reckoned with.”

Both Kipling and his wife Carrie were in poor health in 1930: the author was beginning to suffer from the gastric ulcers which were to kill him in 1936; Carrie had excruciating rheumatism, and had become diabetic.

Their doctor prescribed a sea voyage, and in February 1930 the Kiplings embarked on a West Indies cruise.

“But when they began a tour of the islands, Carrie collapsed with appendicitis,” said Mrs. Stamers-Smith. ” …So they came up from Nassau to Bermuda in the S.S. ‘Lady Rodney’, a mailship regularly plying the route with her sister ship the ‘Lady Somers’, going on to Halifax and Montreal.

“Carrie was taken into the Edward VII Hospital — formerly the Prince of Wales Hospital — where fortunately the appendix formed an abscess which could be dealt with, at least temporarily, by medical rather than surgical means.”

Kipling originally booked into Hamilton’s Bermudiana Hotel but when it became evident the couple would be on the island for some time, he eventually moved to a private guest house run by a Mr Rowley.

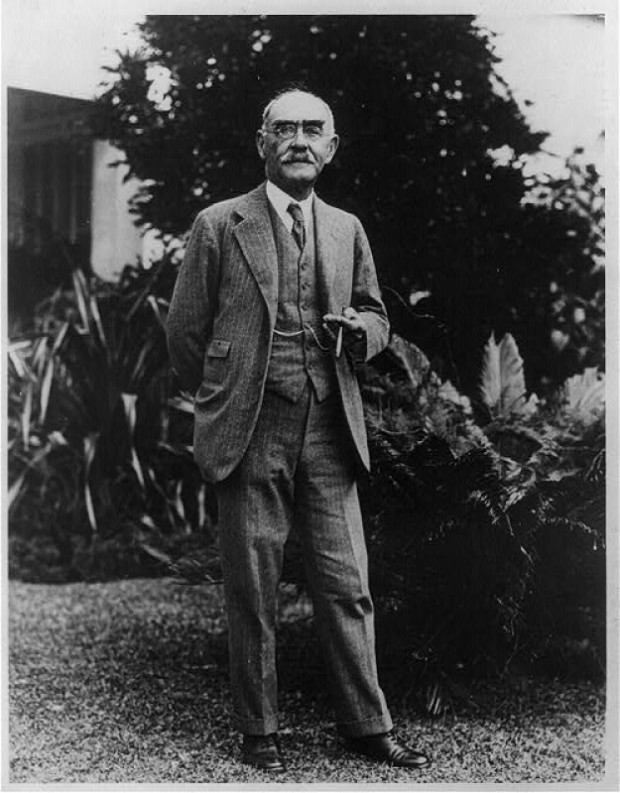

Rudyard Kipling In The Grounds Of The Bermudiana Hotel, 1930

Kipling spent time with his wife at the hospital every day while she was recovering and also visited children in other wards.

“A little girl in the hospital remembered him producing several baby rabbits from his pockets and weaving a story round them,” said Mrs. Stamers-Smith. “When the nurse approached, he swept them away with a conspiratorial wink.

“On his last visit, he took the little girl an elephant-hair and gold bracelet, and gave her mother an antique bon-bon box. The child’s parents noticed that, as they walked to and from the hospital each day with Kipling, he always paused at the war memorial.”

Between visits to his wife [he "would sit cross-legged at the end of the bed, talking energetically and telling vivid stories of what he had been doing," recounted Mrs. Stamers-Smith], Kipling absorbed material about Bermuda and Bermudian life which was later incorporated into his two stories.

“A Naval Mutiny” is an account of a mutiny by a large number of caged parrots in the temporary charge of a time-expired Royal Navy sailor, Winter Vergil; and of the ingenious way the old man quells it by treating the ringleaders, Jemmy and Polyphemus, as he would have treated lower-deck rebels during his service.

“… Kipling uses details from his observation [of Bermuda] to set the rather improbable story on what he had termed an ‘earth-basis’ of fact,” said Mrs. Stamer-Smith. “The local colour is very delicately introduced. ‘Randolph’s boat-repairing yard’ — where Winter Vergil gives his account of the parrots’ mutiny — is approached ‘along the front street to the far and shallow end of the harbour … just off the main road, near the mangrove clump by the poinsettias’. This is Foot-of-the-Lane.

“Mr. Heatleigh — whom the end of the story reveals as a retired admiral who had served afloat with Winter Vergil many years before — watches as ’along the white coral road behind passed a procession of horse-drawn vehicles; for another tripper-steamer had arrived, and her passengers were being dealt out to the various hotels’. Until 1946 there was no motor transport in Bermuda [except army trucks during the Second World War]: islanders used bicycles, carriages and carts; and there were many horses for riding.”

Former Bermuda High School headmistress Mrs. Stamers-Smith — who studied English Literature at Oxford University — said Kipling captured the nuances of the island at the beginning of the modern tourism era in this luminous pen-portait of the island: The “scarlet hydroplane” of an American millionaire, “crowded with nickel fitments and reeking of new enamels”, roars off from her mooring nearby “with outrageous howlings”, so that “the dead-water-rubbish swirled in under the mangrove-stems”; and Heatleigh and Winter Vergil settle down in the sun to talk, as “a breath of warmed cedar came across a patch of gladioli.”

The main characters from “A Naval Mutiny” appear again in “A Sea Dog” along with a newcomer — Mr. Gladstone Gallop, a Bermudian deep-draught pilot descended from Carib Indian slaves.

The main story of “A Sea Dog” is told in flashback and is set aboard a Royal Naval vessel during World War One. “Able Dog” Malachi [otherwise Mike] who, on false evidence, is disrated to “Pup” for fouling the upper deck of the destroyer “Makee-do” while the ship is on convoy duty in the North Sea. After hunting submarines and dealing with a German minelayer, the commander promotes Malachi to “Warrant Dog”" because he had given early warning in the fog of the enemy’s whereabouts.

The 1930s Bermuda Described In Rudyard Kipling’s Two Stories

The story is narrated within a Bermuda setting. The characters are on a trip to test a sloop that has been repaired in Randolph’s boatyard.

She is “known to have been in the West Indies trade for a century”; and Mr. Gallop, her owner, makes his boat “show off among the reefs and passages of coral where his business and delight lay” — on their return, “taking a short-cut where the coral gives no more second chance than a tiger’s paw”.

“As they had gone out into the open sea via the Great Sound and Grassy Bay, a ‘twenty-thousand-ton liner, full of thirsty passengers’, coming in through Two-Rock Passage, had been pointed out by Mr Gallop, who tells his companions that a little ferry, which is also in sight and is recognised as a former North Sea minesweeper, is a better sea-boat than the liner.”

Near the end of the story, Mrs. Stamers-Smith said Kipling cauld not resist one last thrust at the evil effects of Prohibition on visitors to Bermuda: “In an hour, they had passed the huge liner tied up and discharging her thirsty passengers opposite the liquor-shops that face the quay.

“Some, who could not suffer the four and a half minutes’ walk to the nearest hotel, had already run in and come out tearing the wrappings off the whisky bottles they had bought. Mr. Gallop held on to the bottom of the harbour and fetched up with a sliding curtsey beneath the mangroves by the boat-shed …”

I just love these. What amazing footage. Thank you bernews for these gems of our history.